Henry Frick's Paintings

Whenever I visit The Frick Collection in New York City, I marvel at what it must have been like for Henry Clay Frick, whose mansion and art collection were left to the public after his death in 1919, to own three paintings by Johannes Vermeer. When Frick built his home he already knew he intended for it and his large art collection to become a museum someday, but during his lifetime it was a place of residence. One can imagine him on an ordinary weekday morning finishing breakfast and pausing not to look out the window but to contemplate the expression of a Dutch woman from the seventeenth century as captured by the masterful Vermeer.

Johannes Vermeer, Girl Interrupted at Her Music, 1658-59, Oil on canvas

Johannes Vermeer, Mistress and Maid, 1666-67, Oil on canvas

Johannes Vermeer, Officer and Laughing Girl, 1657, Oil on canvas

Johannes Vermeer, sometimes called the Sphinx of Delft, was a man of mysteries even when he was alive. Few people outside of Delft had heard of him, and his output – a total of 35 paintings – was low. Since then, his riveting work has inspired many other artists and writers, including Tracy Chevalier, who wrote Girl With a Pearl Earring. When the painting that inspired her book was shown in the Frick in 2014, visitors waited outside in long lines in subzero temperatures to see the painting. Another painting in the same exhibit, The Goldfinch by Carel Fabritius, drove even more crowds to the exhibit, since it too was the inspiration for a popular book by Donna Tartt. Since The Goldfinch was on loan from The Hague in the Netherlands, most of these folks would only see it once in their lives – a stark contrast to the experience of Frick who lived with his three Vermeer paintings and saw them daily.

Johannes Vermeer, Girl With A Pearl Earring, 1665, Oil on canvas

Carel Fabritius, The Goldfinch, 1654, Oil on panel

The pleasure of having something forever as opposed to experiencing it once and then holding on to its memory is a complicated one. It is easy for me to imagine that Frick must have gazed intently at his beautiful paintings every day, never wearying of their beauty or mystery. I like to think that he savored them with the same attention that those museumgoers lavished on Girl With a Pearl Earring when they had their first and only glimpse of it. I like to think that Frick’s overall quality of life must have been improved merely by his continual access to such great artwork, that his disposition was permanently changed for the better as a result of these possessions.

In all likelihood, however, living with a great piece of art is not like that. According to the hedonic treadmill theory, when something new – either good or bad – enters our lives, most of us adapt to it quickly and then return to our original level of happiness. In other words, though I can’t believe it is true, owning a painting by Vermeer would probably not make me or anyone else significantly happier overall.

I was thinking about this question – that of what it means to experience a particular joy or pleasure repeatedly – when I was reading C. S. Lewis’ Perelandra the other day. Perelandra is the second book in Lewis’ Space Trilogy and also the name of the fictional planet where the story takes place. The main character, Dr. Ransom, arrives on Perelandra and discovers trees with bubbles hanging from them. Each bubble starts tiny and then grows until it eventually bursts. The following is his account of touching one of the bubbles:

“Immediately his head, face, and shoulders were drenched with what seemed (in that warm world) an ice-cold shower bath, and his nostrils filled with a sharp, shrill, exquisite scent that somehow brought to his mind the verse in Pope, ‘die of a rose in aromatic pain.’ Such was the refreshment that he seemed to himself to have been, til now, but half awake. When he opened his eyes – which had closed involuntarily at the shock of moisture – all the colors about him seemed richer and the dimness of that world seemed clarified.”

The pleasure of touching one bubble on the bubble-tree was so great that Dr. Ransom considered throwing himself at the tree so that all the bubbles would burst over him at the same time, but he thought better of it and exercised restraint, knowing that having more of a thing was not necessarily better. He described his thoughts this way:

“But this now appeared to him as principle of far wider application and deeper moment. This itch to have things over again, as if life were a film that could be unrolled twice or even made to work backwards… was it possibly the root of all evil? No: of course the love of money was called that. But money itself-perhaps one valued it chiefly as a defense against chance, a security for being able to have things over again, a means of arresting the unrolling of the film.”

Did Frick love his money? He was certainly a tough businessman. He earned his money first in the coke industry and then later in the steel industry when he became chairman of the Carnegie Steel Company. He was known for being merciless in his dealings with the laborers in the mills, so much so that after a particularly bitter labor strike at one of the steel mills, a man came into his office and shot him. Frick survived, but the story is evidence of the ill will felt toward him.

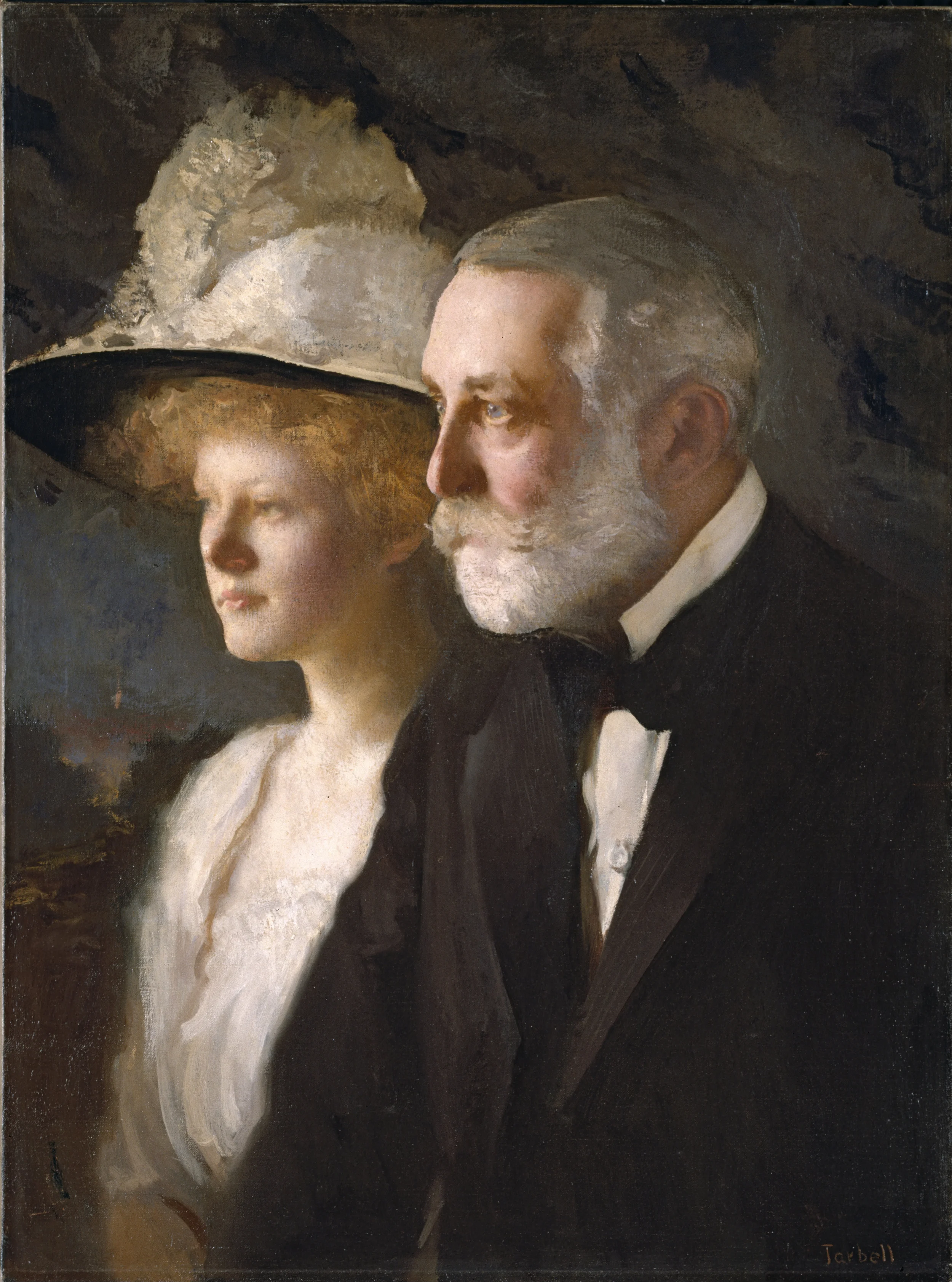

Edmund C. Tarbell, Henry Clay Frick and Helen Frick, 1910, Oil on canvas

Regardless of whether or not he loved it, his money was the reason Frick owned a mansion full of paintings. His money was the reason that he knew these paintings with the same familiarity that ordinary people today might know the sign at the local pizzeria or the pattern of the slightly faded wallpaper in their dining room. And yet, it is worth asking whether, conceivably, those who wait in long lines to see the paintings only once have it so much worse. After all, these pieces will never fade into the fabric of their quotidian lives; their memory of the pieces will always be that of a fresh and startling first impression.

This is not an argument against owning art. A small or even a large art collection is a wonderful thing, particularly when it is shared with others, as The Frick Collection is now. But art, like other possessions, does not necessarily make us happier or better people. Even if we only see a piece of art on rare occasions, perhaps especially if we only see it on rare occasions, we can still bask in its beauty and mystery. We can still understand, for a moment, why the Sphinx of Delft has inspired so many.