Telling All the Truth

“Is the painting realistic?” When I hear this question, I know what people mean. They usually want to know if the painting looks like a perfect copy of the thing it represents. The question is a fair one, but sometimes people follow it up with a judgment. “I’m impressed with things that look real – like a photograph – nothing ‘off’.” I even had a stranger walk by my easel once when I was painting outdoors and interrupt me to say that I hadn’t painted the clouds “as they were in real life.” Never mind the fact that clouds are constantly changing... even if they were static, would the goal of the artist be perfect replication?

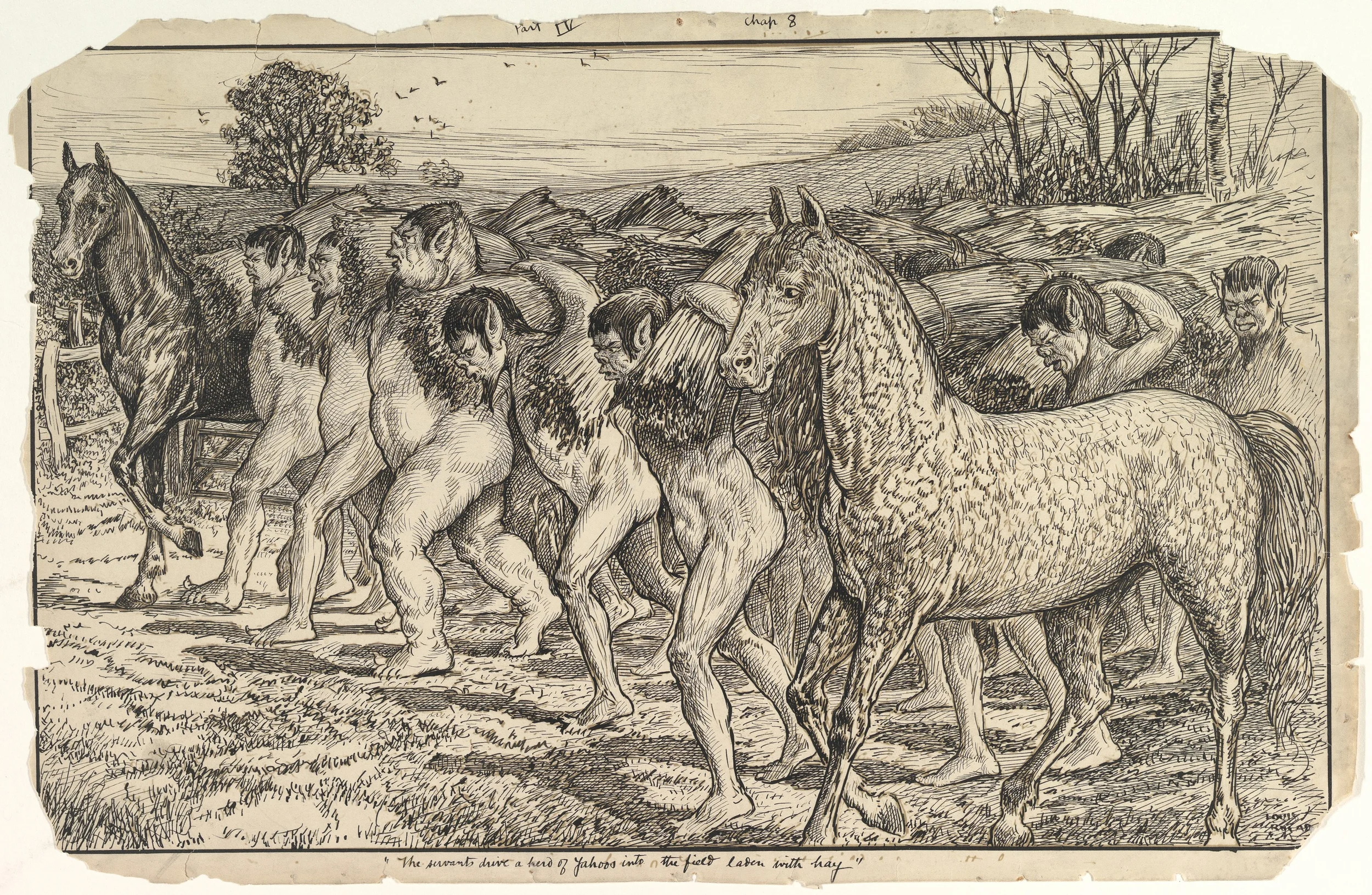

It isn’t hard to recall examples of artists and writers who played with reality. The writer Jonathan Swift comes to mind. In his most famous novel, Gulliver’s Travels, he takes the reader through multiple fictive lands each populated by fantastical characters such as six-inch tall men, sixty-foot tall men, ineffective academicians, and talking horses. (It does seem that one of those four is less absurd than the other three…) Swift’s book exposed the darker side of human nature, and as Gulliver traveled through these varied lands he became increasingly hardened to the reality of how badly human beings sometimes behave. At the end, when he finally arrived in the land of the talking horses, called Houyhnhnms, he preferred the horses to the human-like creatures living there, called Yahoos.

Louis John Rhead, The Servants Drive a Herd of Yahoos into the Field, late 19th - early 20th century, Pen and ink

Swift has been quoted as saying, “Vision is the art of seeing what is invisible to others.” This quote could be interpreted in more than one way. The most obvious is that Swift saw visions of fictional lands in his mind, lands that were invisible to others. More likely, however, the vision he was talking about was his pessimistic vision of humanity. His fictional tales illuminate aspects of human nature that are real but not always apparent.

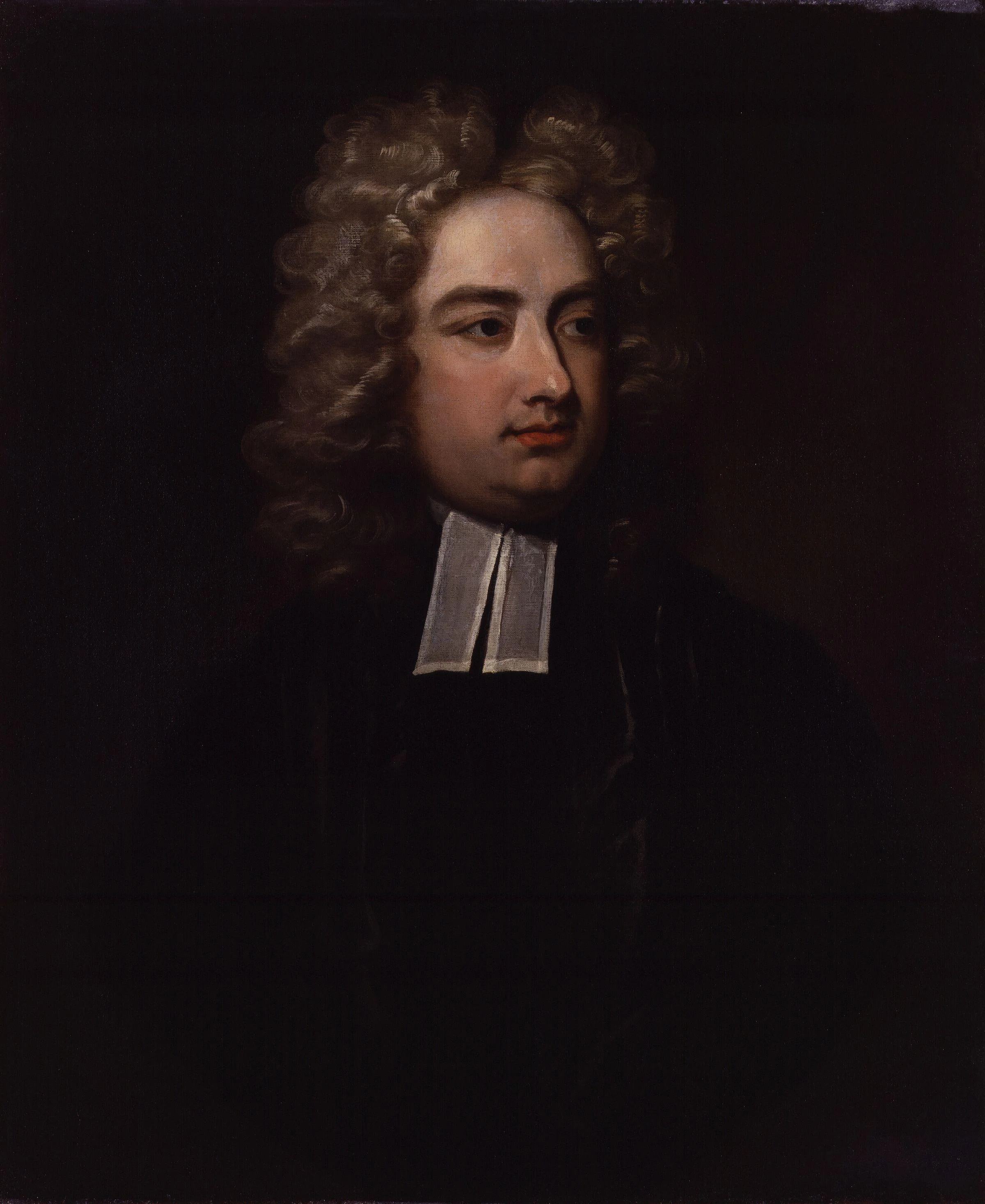

Charles Jervas, Jonathan Swift, 1710, Oil on canvas

When I read Gulliver’s Travels in college, I learned that it was an example of verisimilitude since it has the semblance of truth. As bizarre as Gulliver’s journey was, it felt real enough to me as a reader that I was willing to ride along and see what would happen next. I “believed” in the realistic details of the story enough that I didn’t object to the completely far-fetched aspects of it. My willingness to set aside my incredulity allowed me to see the larger truth of Swift’s work.

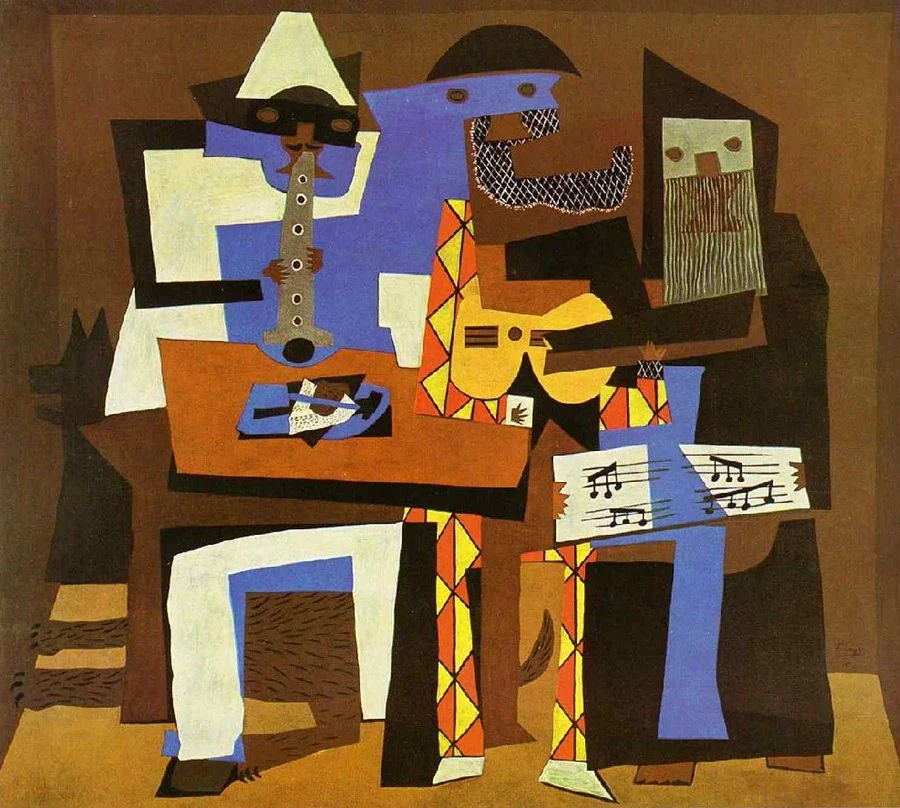

A similar effect plays out in the visual arts. Pablo Picasso’s distorted and fractured forms are almost exactly the opposite what many people would call realistic painting, but he was not unconcerned with the truthfulness of his work. The following is one of his most famous quotes:

“We all know that Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand. The artist must know the manner whereby to convince others of the truthfulness of his lies.”

Like Swift, Picasso used something other than literal representation to show his audience the truth. His paintings are not photorealistic, but they point us toward a real understanding of the things they depict.

Pablo Picasso, Three Musicians, 1921, Oil on canvas

The arts often startle us into a new perspective, a new slant some might say. And yes, I’m talking about Emily Dickinson, who couldn’t go unmentioned here since she is known for writing that we should, "tell all the truth, but tell it slant." I can’t say anything better than she did, so I’ll go ahead and include the entire poem.

“Tell all the Truth but tell it slant –

Success in Circuit lies

Too bright for our infirm Delight

The Truth’s superb surprise

As Lightening to the Children eased

With explanation kind

The Truth must dazzle gradually

Or every man be blind –”

According to Dickinson, part of the reason the truth must be told in slanted and circuitous ways is that the whole of it, the entire blazing, fearsome truth, is too much for us to take in at once. The truth she is writing about here is not the simple, literal truth of making a cloud in the sky look just like a photograph of a cloud in the sky but the complex truth of showing what a cloud (or anything else for that matter) truly is. Capturing the truth of what something truly is at its core is terribly difficult work, and it is far more difficult than merely copying the outward appearance of things. Nevertheless, the paintings and books I most admire are the ones that give me a glimpse - a quick, dazzling flash – of reality.