Disorder and Decorum: Breaking the Rules at the MFA

Parallel exhibits, Beyond Limits and Political Intent, currently share the Henry and Lois Foster Gallery at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Selected from the museum's collection, the work in these shows represents a diversity of media. From bold, red screen prints by Andy Warhol to an airy, white installation by Ernesto Neto, there is not one style on display here, but many. The unifying factor in the shows is not an aesthetic but the way these artists provoke us to question where we stand, both where our physical bodies exist and where we stand ideologically on social issues.

Andy Warhol, Red Disaster, 1963, 1985, Silkscreen on canvas, two panels.

When I made the decision to go see the work, I had imagined myself walking quietly through the gallery, pausing now and then to read a description or write something down. To my surprise and chagrin, the museum was also hosting a free event for the Lunar New Year, so the building was pulsating with the energy of children, parents, babies in strollers, and guards anxious to protect the valuable works on display. More than once I heard a "No!" and jerked my head around to see a museum employee striding over toward a miscreant child. Those alarms, which usually go off when an inquisitive guest leans in too closely, had become a chorus of unheeded caution as tiny museum-goers pranced around the work, stepping over lines and reaching out to touch things. At one point, I stood still for what was apparently long enough to arouse suspicion and a guard, set on edge by the general atmosphere, approached me, rather aggressively, to ask, "What are you looking for?"

A couple hundred juice boxes and slices of cheese pizza were in order. Sadly, the cafeteria on the garden level was closed, so people had formed a long line outside the little cafe by the bookstore. I, too, had planned on eating something, but seeing the slowness of the line and the general din surrounding the area, I decided to walk down to the empty, foodless, and blissfully quiet cafeteria space where I ate the Payday candy bar I keep in my purse for such occasions.

Strengthened, I returned to the gallery and resolved to see it for what it was: an important, albeit raucous, pair of exhibits. In the first show, Political Intent, a series of Kara Walker's silhouettes stretched across a dark gray wall. Narratively ambiguous, her work shows happy domesticity and sexual violence coexisting as black and white human shapes intertwine. Walker draws on the nineteenth-century, American tradition of decorating one's home with sweet, innocent cut-paper silhouettes, but her work acknowledges the ugly side of that era and forces us to stop prettifying the truth of the African American experience. There's something physically discomforting about her work, since it both reduces the bodies of human beings into flat stereotypes and, also, simultaneously, draws attention to the violation of those bodies.

Kara Walker, The Rich Soil Down There, 2002, Cut paper and adhesive on painted wall

Adjacent to Walker's work, there was a video, Melons (At a Loss), by Patty Chang in which she cut into her blouse with a knife to expose a large melon in the place of her breast. She proceeded to scoop out the contents of the melon and place them on a plate. Calling women's breasts melons is both vulgar and cliché, but the video was neither. It was cringe-inducing, but mainly because of the sharp knife and the strangeness of seeing someone remove what appeared to be the contents of her own body.

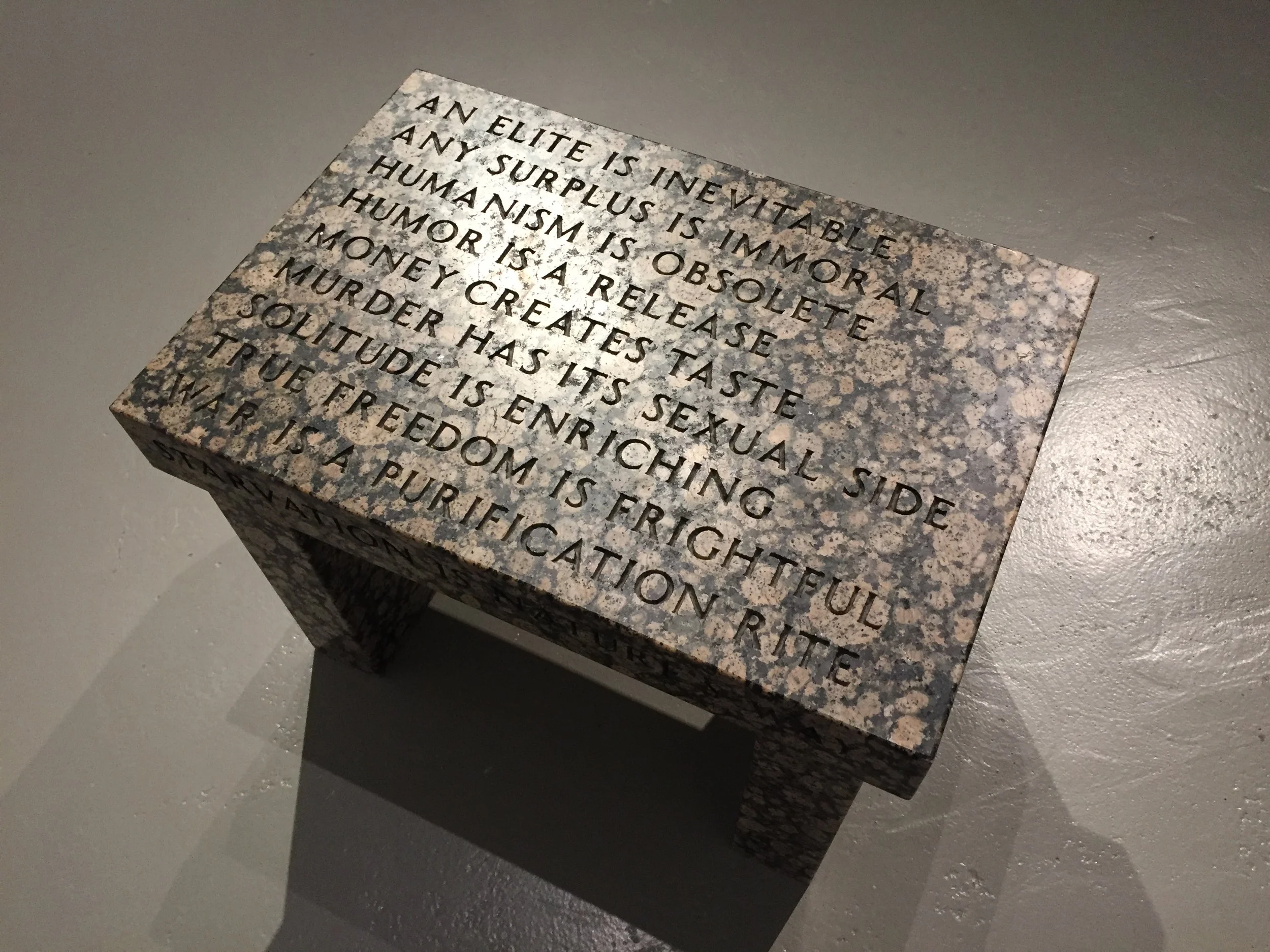

Jenny Holzer's Truism Footstool was also part of Political Intent. It was inscribed with truisms, including, "An elite is inevitable." and "Any surplus is immoral." The sign near the stool said to sit on it, but it was too low to be comfortable. I began to wonder whether the seat was meant to lift people up or bring them down. A footstool, after all, is often used for reaching high things, and the piece could be interpreted as a symbol of the foundation many power-seekers build their careers upon. Either way, the pedestrian way the truisms were stacked one on top of another made them seem meaningless and crass, and using the stool made me feel complicit with the statements.

Jenny Holzer, Truism Footstool, 1988, Baltic brown granite

Moving across the hall to Beyond Limits, I encountered Mona Hatoum's Grater Divide. The larger-than-life cheese grater with its human scale and sharp blades looked more like an instrument of torture than a cooking utensil, and, though I knew the artwork was not dangerous, I gave it a wide berth as I walked around it. As its title indicates, the piece is about division, and it functions as a screen between the two exhibits. The piece is also about Hatoum's experience as an exile from Lebanon during its civil war. War makes the ordinary things of home into something ghastly and strange, just as she does with this enlarged grater.

Mona Hatoum, Grater Divide, 2002, Patinated mild steel

In the next room, I walked under Ernesto Neto's Prisma Branco, a latticework of drooping, biomorphic forms. Both heavy and light, the large installation hangs pendulously from the ceiling but cannot possibly weigh more than ten or fifteen pounds, seeing as it is made from thin, nylon fabric. The pink and blue tendrils hung at about the height of my eyes, and while I resisted the urge to reach out and grab one, many of the children in the space did not. In the description of the work on a nearby wall, I read that the pink and blue forms were meant to symbolize the fundamental, biological connections between human beings, and it did seem that the piece exerted a force pulling people together under it.

Ernesto Neto, Prisma Branco, 2008, Polyamide nylon and glass beads

Another piece in Beyond Limits, Yoan Capote's Abstinencia (politics), shows a set of cast bronze hands that spell out the word politics in sign language. He made the casts from the hands of many individual Cubans who feared openly discussing issues in their country, so the piece represents discreet, collective resistance. Modest in scale and subtler in its message, the piece fit the theme of the exhibit but spoke using a silent language.

Yoan Capote, Abstinencia (politica), 2011, Cast bronze and unique reproduction made from original watercolor print

Though they exist within the lofty halls of a museum, the works in these shows are not meant purely for aesthetic contemplation. Perhaps it is just as well that I visited on a day when peaceful reflection was out of the question. The crowds of fussy, hungry children and tired parents were not unlike those I had seen at the Women's March in Boston just two weeks ago, and I was reminded that political engagement is not tidy, easy work. I wonder, in fact, if some of the artists in the shows would have been happy to see kids transgressing the norms of museum behavior since their art is not meant to exist within the confines of society's expectations. In that sense, the loss of decorum was appropriate, and while I still hope to eat a nice salad and relax the next time I visit, I'm glad yesterday was a disorderly day at the museum.