Living Memorials in the Kingdom of Forgetting

My mother and I felt unsteady climbing the unnaturally large stairs leading up to The Memorial to the Victims of Communism in Prague. The flat portions of the stairs were slanted slightly downward, so, to avoid slipping, I decided to walk sideways. Once I’d turned, I found myself looking directly at the bronze strip of text running down the center of the stairs. I couldn’t read the Czech words, but later I found out they were a list of estimated numbers for those affected by Communism.

- 205,486 arrested

- 170,938 forced into exile

- 4,500 died in prison

- 327 shot trying to escape

- 248 executed

Sculptor: Olbram Zoubek, Architects: Jan Kerel and Zdeněk Holzel, Memorial to the Victims of Communism, 2002

Even before I knew what the words meant, I could already sense the gravity of the memorial, since the sculptural aspect of it was unmistakably a representation of suffering. Like automatons falling into formation, seven, identical, bronze figures descend the staircase. Naked, thin, and hollow, the men look like broken shells of human beings. The one at the front is whole, but each figure behind him looks increasingly less human since portions of their bodies appear to have been torn away. At the back of the line is a single, narrow, abstracted foot form. Seen apart from the others, it might not even be identifiable. The largeness of the stairs added to the overall effect, since the task of approaching the figures was itself arduous, and something of their exhaustion had crept into my own body by the time I got to the top.

Sculptor: Olbram Zoubek, Architects: Jan Kerel and Zdeněk Holzel, Memorial to the Victims of Communism, 2002

A couple weeks before the trip I listened to an interview on the podcast On Being with Dr. Bessel van der Kolk, a psychiatrist in Boston who works with survivors of trauma. Dr. van der Kolk spoke of a conversation he had early on in his career with a man who had survived the Vietnam War only to be frequently woken by terrible nightmares after his return home. He prescribed him medication for the nightmares but discovered later that his patient wasn’t taking the medication. When he asked him why not, the patient said something which touched him deeply. He said, “I did not take your medicines because I realized I need to have my nightmares, because I need to be a living memorial to my friends who died in Vietnam.”

This burden, that of living as a memorial to the dead, is not unique to that veteran. There are people in every community who continue to suffer because of what they lived through in the past, and while their nightmares are their own, we all bear some responsibility to remember the past. Walking the streets of Prague, I wondered how many of the people I saw could have told me stories about their lives during communism. Did the women my age, who were four years old when communism ended, remember it at all? What would the women my mother’s age, most of whom spoke Czech and Russian (but not English), have told us if we could have spoken to them in a language they understood?

Preserving memories is an inherently powerful act, since it allows the past to inform the type of future we want to create. When living under an oppressive government, it is also a subversive act, since it means the government doesn’t have exclusive rights to the peoples’ stories and self-understanding. Perhaps it is not surprising, then, that the period after 1968 in Czechoslovakia has become known as the "era of forgetting". In the spring of 1968, Czechoslovakia’s leader Alexander Dubček attempted to reform his country’s communism, and he loosened the restrictions on travel and speech. The Soviets, however, were not pleased with these changes, and in August of that year Warsaw Pact allies invaded Czechoslovakia and began a process of “normalization”, in which the reforms were reversed and history was rewritten. Soon, the country became known as the “Kingdom of Forgetting”, since there was a concerted effort to erase aspects of Czech national identity and communal memory which would have made Soviet rule more abhorrent to the people than it already was.

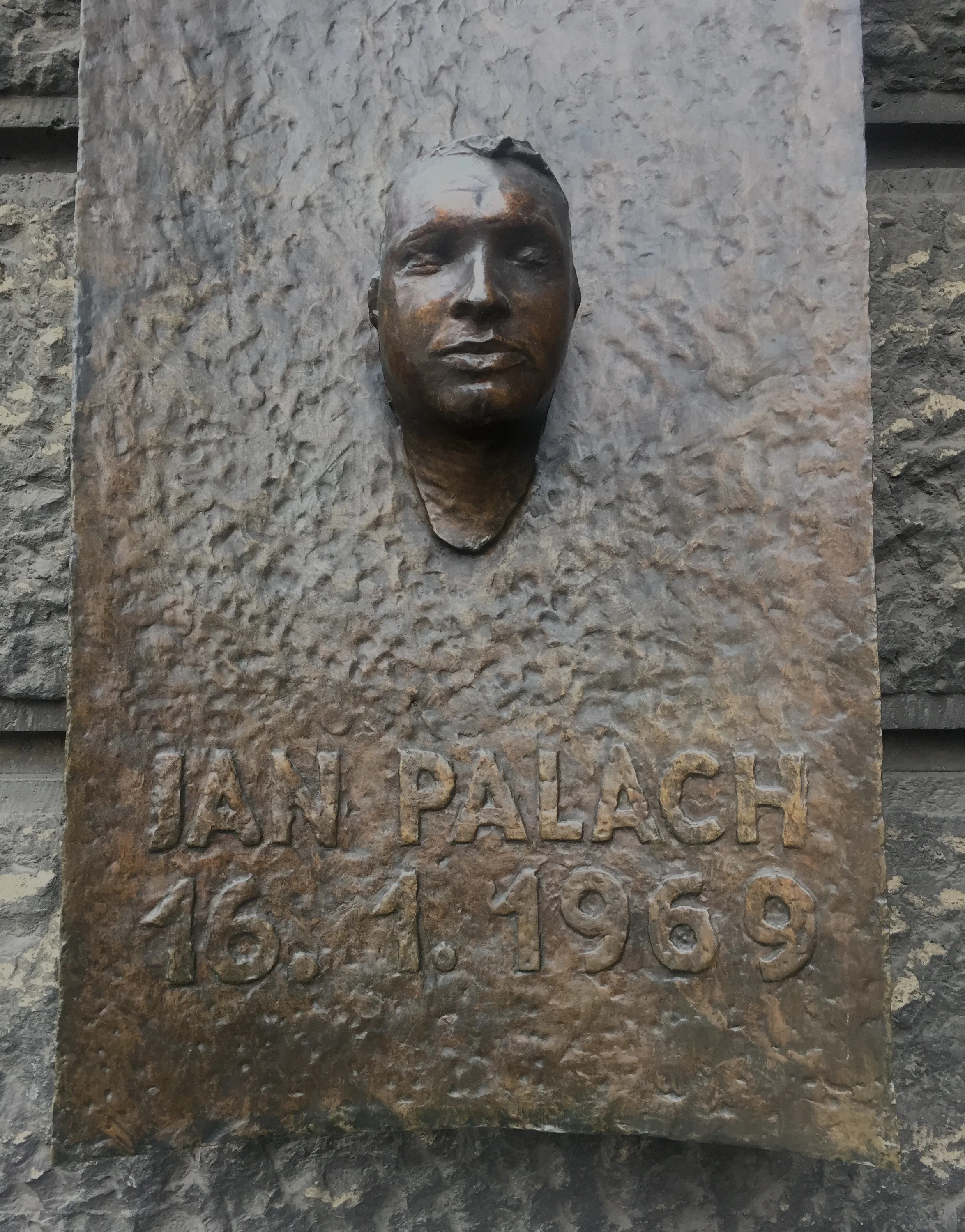

It was in this climate in 1969 that Jan Palach, a student at Charles University in Prague, made the decision to set his own body on fire and die in protest of the way people had given in to the invasion. His act might seem futile, but his goal – to spur his countrymen on to resist the Soviets – was admirable, and his courage was undeniable. Hundreds of thousands of Czechs attended his funeral, and they, the people who acknowledged what he had done, became the living memorials to his sacrifice. For these people, Palach’s grave in Prague was a pilgrimage site. Not surprisingly, the secret police pressured his family into exhuming the body and cremating it, so that the grave, such a powerful threat to their kingdom of forgetting, would cease to exist.

Today, twenty-eight years after the end of communism in Prague, there is a lasting memorial to Jan Palach’s sacrifice in the place where his burning body fell to the ground. The cobbled pavement there in Wenceslaus square swells into two mounds – one for him and one for another young man, Jan Zajíc, who also set himself on fire in defiance of Soviet oppression. Connecting the two mounds is a bronze cross. On the day we visited the site, there were also flowers and candles on the site. It was an ordinary Tuesday, so I can only imagine how many more flowers we might have seen if we had visited on the anniversary of his death.

Memorial to Jan Palach and Jan Zajíc in Wenceslaus Square

On our last day in Prague we went to see one final memorial, the death mask of Jan Palach, which is on the façade of Charles University’s Faculty of Philosophy where he once studied history. Both his youth and his burn wounds are evident in the mask, so it is hard not to cringe while looking at it. Still, the place is primarily a lively one. Outside the building, a few students lit up cigarettes in the chilly March air. Inside, others clustered in small groups chatting or sat at small tables with their books. And on the stairs, one leapt effortlessly upward, headed toward class and a future where he and his classmates will carry the responsibility of remembering their country’s past.

Jan Palach's death mask taken by Olbram Zoubek