Seeing the Invisible War

Flying over New York City this past Friday night, I saw the tiny Statue of Liberty down below, its bright lights flickering against the dark water around it. Next to me sat a young woman, and I pointed out the monument, so perfectly framed by our shared window, to her. This was the beginning of one of those happily awkward conversations that sometimes happen on planes. I discovered she was a senior in college visiting her husband who was stationed in New Jersey for spring break. They were going to spend the night in a hotel near the airport and then travel down to Disney World together. She talked about her eagerness to graduate and spend more time with him but also about her worries – would he be deployed? What would she do if he were?

We landed, and I sped off to the gate of my flight to Boston. I had missed the flight because of delays in New York, and in the flurry of getting booked onto another flight and arranging a later pickup from the Boston airport, I forgot about her.

Sunday afternoon I went to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and looked at one of their current exhibits: Over There! Posters from World War I. Brightly colored propagandistic images, images once used to convince Americans to enlist, give money, eat less bread, and even die for their country were prettily matted and framed in the galleries of the museum. There’s a dissonance to displays like this. The setting is so genteel – museum-goers, some of them still wearing their nice church clothes, strolling about in a space that cost them a twenty-five dollar ticket to enter. Squint your eyes and don’t read the text on the brilliantly colored posters, and nothing seems awry – just a group of wealthy people looking at beautiful things.

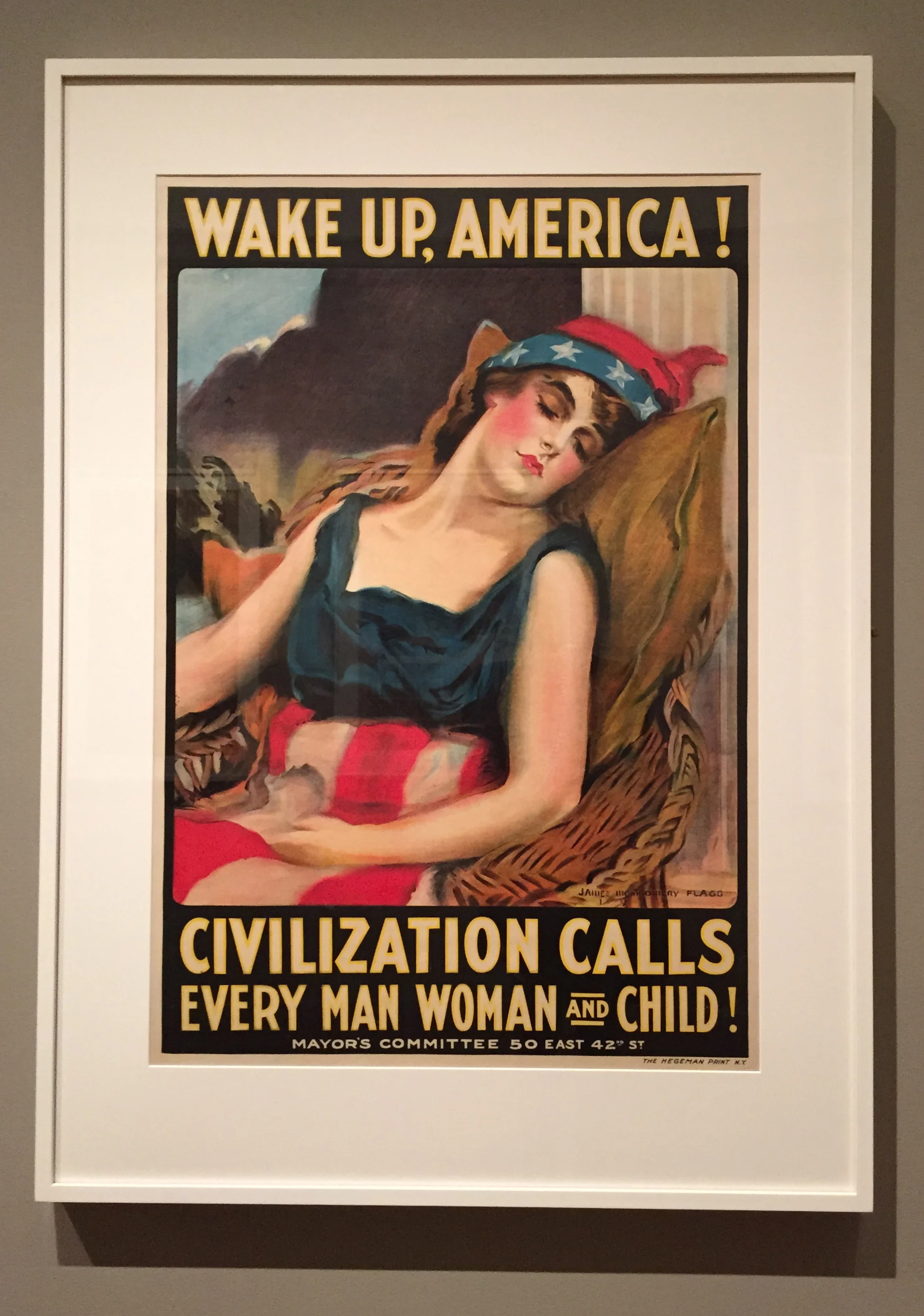

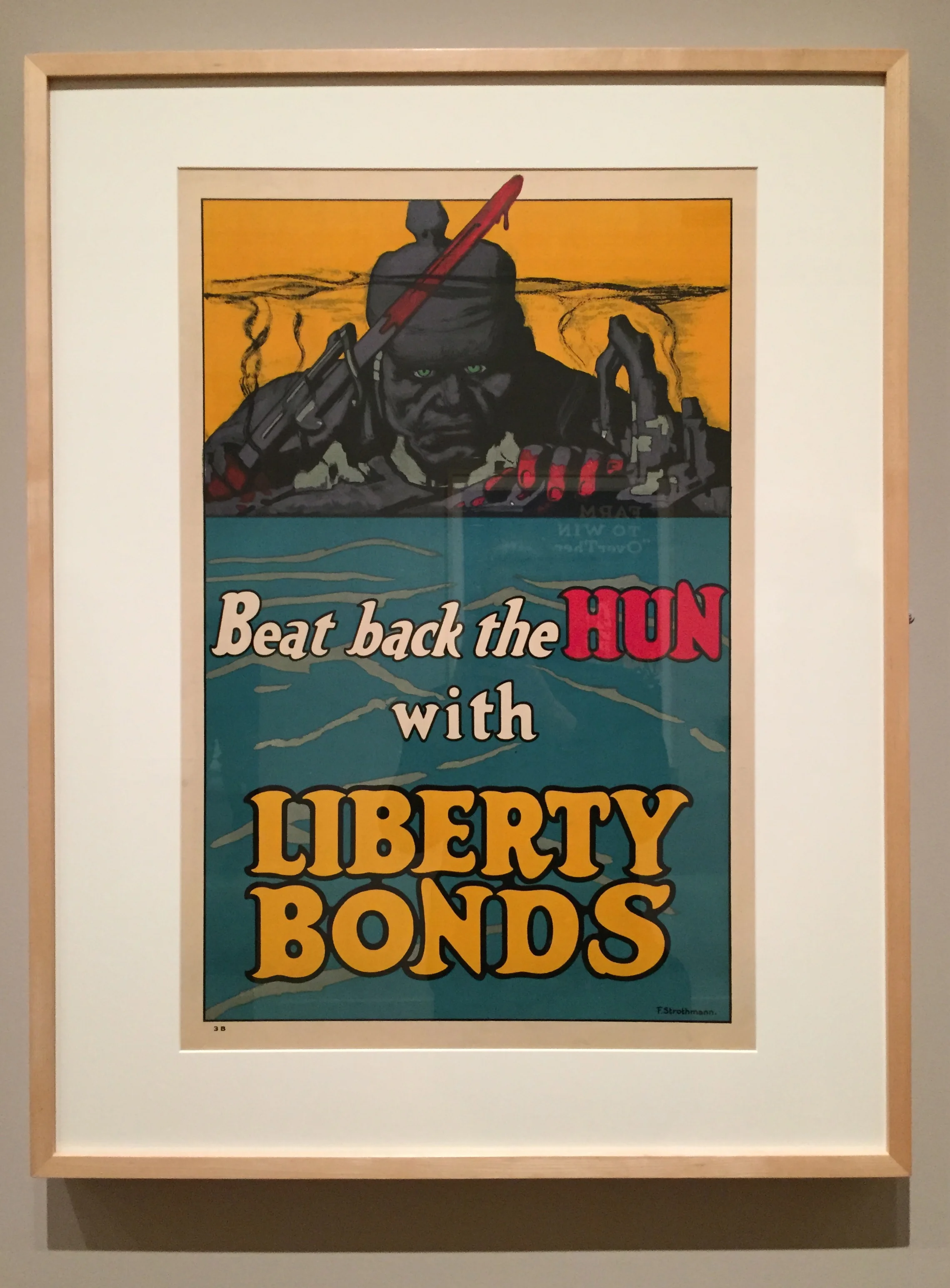

But it is hard to squint that much. The text is large and designed to be read. “WAKE UP AMERICA!” reads one. “FOR VICTORY, BUY MORE BONDS,” reads another. “Beat back the HUN with LIBERTY BONDS!” “JOIN THE AIR SERVICE AND SERVE IN FRANCE! DO IT NOW!” Cacophonies of demands reverberate across the walls of the gallery.

James Montgomery Flagg, Wake Up, America! - Civilization Calls Every Man, Woman, and Child!, Color Lithograph, 1917

Fred Strothmann, Beat Back the Hun with Liberty Bonds, Color Lithograph, 1918

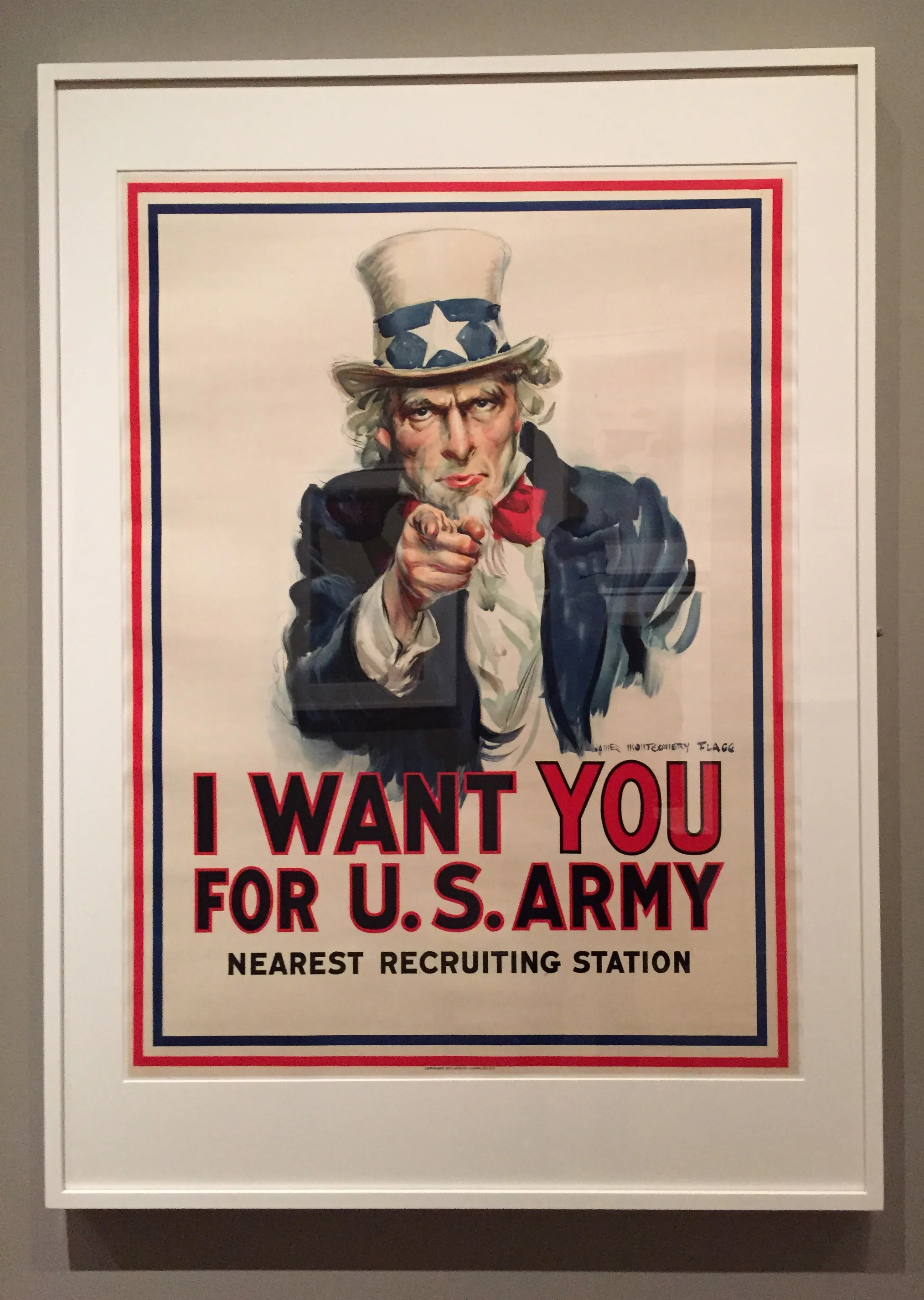

The posters were created as a part of a campaign from the Committee on Public Information. In 1917 Woodrow Wilson established this committee and gave them the assignment of inspiring the people to patriotism and sacrifice. Charles Dana Gibson, who was also the president of the New York Society of Illustrators, headed one division of this committee, the Division of Pictorial Publicity. The artists Gibson gathered together to make these posters were volunteers who donated their talents and created some of the most striking images of the era. Some of them, particularly James Montgomery Flagg’s I Want You for (the) U.S. Army, are now iconic.

James Montgomery Flagg, I Want You for U.S. Army, Color Lithograph, 1917

This is not the first time these posters have been displayed in the museum. John T. Spaulding gave this collection to the museum in the summer of 1937, and they were first displayed in October 1938. A visitor seeing that display would have known that another conflict was about to begin in Europe. He would have also remembered the sacrifices made by ordinary citizens during the First World War. He may have been wealthy enough not to suffer personally during the Great Depression, but the reality of it was all around him. In that context, these posters must have cast an ominous shadow over his thoughts about the future.

On the walls of the current exhibit small notes from the curator, Patrick Murphy, are printed for visitors to read. In one of them Murphy reflects on his experience of putting together this exhibition.

“While sifting through the Spaulding collection of WWI posters in preparation for this exhibit, I was struck by the notable differences in Americans’ experience of war then and now. In recent years, it has been possible for many of us to forget that we were at war in Iraq and Afghanistan. In 1917 and 1918, as these posters attest, the call for personal sacrifice – whether through the conservation of food, purchase of Liberty Loans, or support of the Red Cross – permeated every aspect of life on the home front.”

Murphy’s words took me back to my conversation on the plane from several days before, but it also reminded me of many other similar moments I’ve had in airports. As a Midwesterner who was in school on the East Coast from 2003-2009, I spent a lot of time in airports during those years. Those times were always the ones when I realized most acutely that we were at war. During the rest of the semester I was stressed out with all the homework I had to do, but when I got to the airport to travel home for Thanksgiving and Christmas I saw people my age who were more than stressed out; they were traumatized. Hollow-eyed men and women wearing fatigues sat next to me in the airport while I (and many other college kids in Boston Logan Airport) sipped my Starbucks gingerbread latte and read my book. The posters on the walls encouraged us not to plant and raise our own vegetables in a victory garden but to try the peppermint and eggnog flavored lattes too.

James Montgomery Flagg, Sow the Seeds of Victory! - Plant and Raise Your Own Vegetables, Color Lithograph, 1918

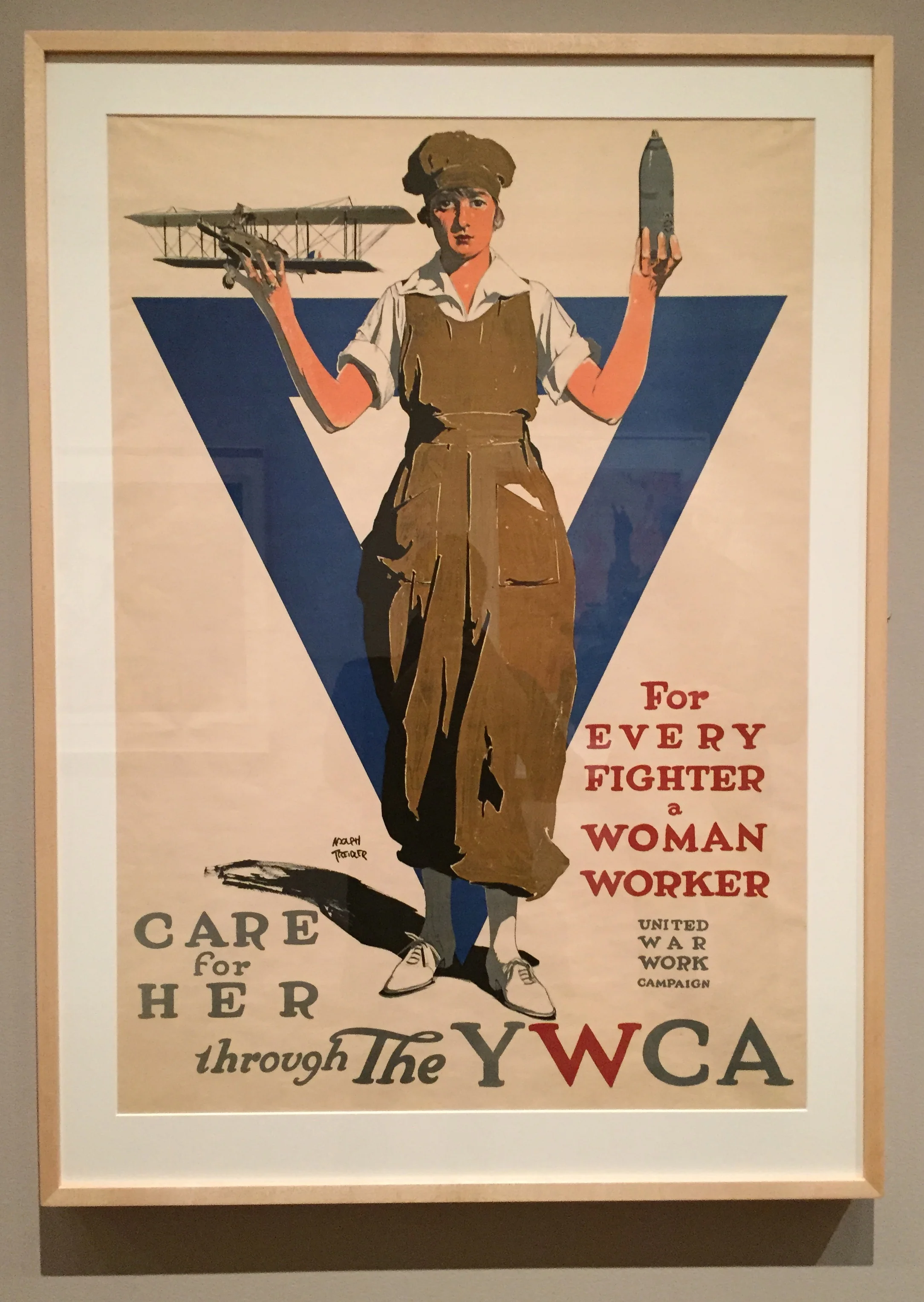

I’ll probably never know what we with our over-stuffed backpacks and college sweatshirts looked like to them. What I do know that is that war wasn’t always so tidily quarantined away from civilian life. As these posters make apparent, there was a time when young people were not so neatly divided into those who fought and those who stayed home. Any young man could be drafted, and young women were encouraged to do their part as well by working in a munitions plant or volunteering with various organizations.

Adolph Treidler, For Every Fighter a Woman Worker - United War Work Campaign - Care for Her through the YWCA, Color Lithograph, 1918

In saying this I don’t mean to be nostalgic about the posters or the world as it was in 1917. While the posters made people aware of the war they were fighting, they also hid its horrors. An image of a sailor riding a torpedo through the water makes war look like an exciting adventure, a roller coaster of good times and proof of one’s great manliness. Needless to say, the actual war was not like that. Nevertheless, what I like about these posters, and what I think they offer to contemporary viewers, is the reminder that the way some of us blithely go about our business during war is somewhat unique to our time.

Richard Fayerweather Babcock, Join the Navy - The Service for Fighting Men, Color Lithograph, 1917

Art Inside Auschwitz

It's Christmas Break, and while I probably ought to be reading something cheery and seasonal, instead I've been re-reading Man's Search for Meaning, Viktor Frankl's memoir about his harrowing experiences in the Auschwitz and Dachau concentration camps during World War II. Since he had practiced psychiatry before the war, Frankl had a unique perspective on both his own suffering and his fellow prisoners' suffering. The first part of his book describes in gritty detail the life of the prisoners, and the second part lays out Frankl's psychological theory. Frankl's profound personal suffering gives his words gravity, and it is hard to ignore even the most counterintuitive of his insights.

One of those insights is that the prisoners' suffering did not blunt their sensitivity to beauty but rather enhanced their experience of the wonders of nature. Frankl describes it this way:

“As the inner life of the prisoner tended to become more intense, he also experienced the beauty of art and nature as never before. Under their influence he sometimes even forgot his own frightful circumstances. If someone had seen our faces on the journey from Auschwitz to a Bavarian camp as we beheld the mountains of Salzburg with their summits glowing in the sunset, through the little barred windows of the prison carriage, he would never have believed that those were the faces of men who had given up all hope of life and liberty. Despite that factor - or maybe because of it - we were carried away by nature’s beauty, which we had missed for so long.”

It's hard to know exactly what these men saw, but it was probably something like this picture of the Berchtesgaden valley near Salzburg. The view is breathtaking indeed, but would it really have been even more stunning to a person who was cold, starving, crammed into a foul-smelling train, and expecting to die soon?

Frankl tells us it was. He also tells another story in which one of his friends drew his attention to a view which reminded him of an Albrecht Durer watercolor. The idea that one could even think about watercolors from the Renaissance at such a time is hard to conceive of, but Frankl tells us just that.

“In camp, too, a man might draw the attention of a comrade working next to him to a nice view of the setting sun shining through the tall trees of the Bavarian woods (as in the famous water color by Durer), the same woods in which we had built an enormous, hidden munitions plant.”

Albrecht Durer, Pond in the Wood, Watercolor, 1496

In some cases, experiencing beauty seems to give the prisoners enough energy to go on. Frankl tells of one evening when they were all lying on the floor of their hut, dead tired and motionless. And yet when another prisoner ran into their hut and told them that there was a beautiful blood red sunset outdoors, they pulled themselves up to go see what all the fuss was about. After several minutes of silently standing outdoors in presence of this glory one prisoner remarked, "How beautiful the world could be!"

In another story, Frankl recounts a day when he was out in the trenches and, in his words, "struggling to find the reason for my sufferings, my slow dying." He imagined that he was speaking with his wife from whom he had been separated. While he was conversing with her in this way, he had a spiritual experience of beauty. He said:

“I sensed my spirit piercing through the enveloping gloom. I felt it transcend that hopeless, meaningless world, and from somewhere I heard a victorious “Yes” in answer to my question of the existence of an ultimate purpose. At that moment a light was lit in a distant farmhouse, which stood on the horizon as if painted there, in the midst of the miserable grey of a dawning morning in Bavaria. ‘Et lux in tenebris lucet’ - and the light shineth in the darkness.”

This phrase that Frankl uses, et lux in tenebris lucet, is taken from the Gospel of John. The full sentence in English is "The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it." The light here is a reference to Christ. Truthfully I'm not sure why Frankl, a Jewish prisoner, chose words from the New Testament, but regardless of his reasons, I think it is clear why they fit his situation. There he was in place where darkness seemed to have overcome anything resembling light or hope, and yet he was able to hang on to a sense of meaning and purpose. The darkness had not overcome the light.

Earlier I said that this book is an unusual choice for this time of the year, but maybe it is not. Advent is the season when Christians celebrate the fact that, as the prophet Isaiah wrote, "The people walking in darkness have seen a great light; on those living in the land of deep darkness a light has dawned." The fact that prisoners suffering in concentration camps were able to see beauty in the commingling reds and blues of a sunset is exactly what this time of year is about. It's about hope and comfort entering even the bleakest corners of the world.

In one of his final stories about the prisoners' relationship with art and beauty, Frankl writes about the artwork the prisoners themselves made while they were imprisoned. Naturally they had limited resources, but they nevertheless managed to be creative. Sometimes they would clear out a hut, create a stage with a couple wooden benches pushed together, and have a show. People recited poetry, sang songs, and told jokes. These events were so important to some prisoners that, in spite of their malnourishment and fatigue, they would forgo a meal in order to attend a gathering.

For those of us whose refrigerators are stocked with rich, spicy eggnog and expensive Christmas hams, this is a hard thing to imagine. We are rarely in the position of choosing between food, the company of friends, and things of beauty. We can, it seems, have it all. And yet, even in our warm, cheerily decorated homes, we know a little bit about the darkness that is sometimes a part of life, and so it is not surprising to us that there are things we as humans need more than physical sustenance. We need beauty, hope, meaning, and art. We need friends who point out the the things around us that are worth looking at. We need opportunities to use our creativity. Most of all, we need light in the darkness.