Art Inside Auschwitz

It's Christmas Break, and while I probably ought to be reading something cheery and seasonal, instead I've been re-reading Man's Search for Meaning, Viktor Frankl's memoir about his harrowing experiences in the Auschwitz and Dachau concentration camps during World War II. Since he had practiced psychiatry before the war, Frankl had a unique perspective on both his own suffering and his fellow prisoners' suffering. The first part of his book describes in gritty detail the life of the prisoners, and the second part lays out Frankl's psychological theory. Frankl's profound personal suffering gives his words gravity, and it is hard to ignore even the most counterintuitive of his insights.

One of those insights is that the prisoners' suffering did not blunt their sensitivity to beauty but rather enhanced their experience of the wonders of nature. Frankl describes it this way:

“As the inner life of the prisoner tended to become more intense, he also experienced the beauty of art and nature as never before. Under their influence he sometimes even forgot his own frightful circumstances. If someone had seen our faces on the journey from Auschwitz to a Bavarian camp as we beheld the mountains of Salzburg with their summits glowing in the sunset, through the little barred windows of the prison carriage, he would never have believed that those were the faces of men who had given up all hope of life and liberty. Despite that factor - or maybe because of it - we were carried away by nature’s beauty, which we had missed for so long.”

It's hard to know exactly what these men saw, but it was probably something like this picture of the Berchtesgaden valley near Salzburg. The view is breathtaking indeed, but would it really have been even more stunning to a person who was cold, starving, crammed into a foul-smelling train, and expecting to die soon?

Frankl tells us it was. He also tells another story in which one of his friends drew his attention to a view which reminded him of an Albrecht Durer watercolor. The idea that one could even think about watercolors from the Renaissance at such a time is hard to conceive of, but Frankl tells us just that.

“In camp, too, a man might draw the attention of a comrade working next to him to a nice view of the setting sun shining through the tall trees of the Bavarian woods (as in the famous water color by Durer), the same woods in which we had built an enormous, hidden munitions plant.”

Albrecht Durer, Pond in the Wood, Watercolor, 1496

In some cases, experiencing beauty seems to give the prisoners enough energy to go on. Frankl tells of one evening when they were all lying on the floor of their hut, dead tired and motionless. And yet when another prisoner ran into their hut and told them that there was a beautiful blood red sunset outdoors, they pulled themselves up to go see what all the fuss was about. After several minutes of silently standing outdoors in presence of this glory one prisoner remarked, "How beautiful the world could be!"

In another story, Frankl recounts a day when he was out in the trenches and, in his words, "struggling to find the reason for my sufferings, my slow dying." He imagined that he was speaking with his wife from whom he had been separated. While he was conversing with her in this way, he had a spiritual experience of beauty. He said:

“I sensed my spirit piercing through the enveloping gloom. I felt it transcend that hopeless, meaningless world, and from somewhere I heard a victorious “Yes” in answer to my question of the existence of an ultimate purpose. At that moment a light was lit in a distant farmhouse, which stood on the horizon as if painted there, in the midst of the miserable grey of a dawning morning in Bavaria. ‘Et lux in tenebris lucet’ - and the light shineth in the darkness.”

This phrase that Frankl uses, et lux in tenebris lucet, is taken from the Gospel of John. The full sentence in English is "The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it." The light here is a reference to Christ. Truthfully I'm not sure why Frankl, a Jewish prisoner, chose words from the New Testament, but regardless of his reasons, I think it is clear why they fit his situation. There he was in place where darkness seemed to have overcome anything resembling light or hope, and yet he was able to hang on to a sense of meaning and purpose. The darkness had not overcome the light.

Earlier I said that this book is an unusual choice for this time of the year, but maybe it is not. Advent is the season when Christians celebrate the fact that, as the prophet Isaiah wrote, "The people walking in darkness have seen a great light; on those living in the land of deep darkness a light has dawned." The fact that prisoners suffering in concentration camps were able to see beauty in the commingling reds and blues of a sunset is exactly what this time of year is about. It's about hope and comfort entering even the bleakest corners of the world.

In one of his final stories about the prisoners' relationship with art and beauty, Frankl writes about the artwork the prisoners themselves made while they were imprisoned. Naturally they had limited resources, but they nevertheless managed to be creative. Sometimes they would clear out a hut, create a stage with a couple wooden benches pushed together, and have a show. People recited poetry, sang songs, and told jokes. These events were so important to some prisoners that, in spite of their malnourishment and fatigue, they would forgo a meal in order to attend a gathering.

For those of us whose refrigerators are stocked with rich, spicy eggnog and expensive Christmas hams, this is a hard thing to imagine. We are rarely in the position of choosing between food, the company of friends, and things of beauty. We can, it seems, have it all. And yet, even in our warm, cheerily decorated homes, we know a little bit about the darkness that is sometimes a part of life, and so it is not surprising to us that there are things we as humans need more than physical sustenance. We need beauty, hope, meaning, and art. We need friends who point out the the things around us that are worth looking at. We need opportunities to use our creativity. Most of all, we need light in the darkness.

What We Already Know

Not too long ago The Atlantic posted a video about why pop music is so much louder and less varied than it used to be. The video is worth watching, but the gist of it can be boiled down to one fact: music labels produce these songs because we listen to them. In the fifties a hit song was chosen by executives who liked the song and paid radio stations to play it, but now music labels make decisions based on data from listeners. Every time one of us buys a song on iTunes or streams a song on Spotify, we send the music labels a message about the kind of music we are likely to buy in the future. What kind is that? Most us buy songs we've heard before, because these songs are the easiest for the brain to process. In general, we like things better when they require less of us. Music labels have gotten the message, and that's why much of what they produce is as contentless and easy to consume as a giant soda.

In one sense this is a new problem, since even ten years ago there was more variety in pop music than there is today. In another sense, it's an age-old problem. People have always found it easier to enjoy and consume what they already understand. New and challenging material takes awhile to catch on. Innovators must both come up with a new idea and convince the public that it is superior to what they already have.

History is full of stories that fit this paradigm, but one of the most striking comes from France in the late nineteenth century. The Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in France was subsidized by the government and provided artists with both instruction and opportunities to exhibit their work. The training artists received there was excellent, but it was narrow in its focus. While artists did learn to paint traditional subjects in a polished, naturalistic manner, they did not have the opportunity to experiment with new techniques or subject matter. Adolphe-William Bouguereau is a good example of an artist trained in this manner, and his painting The Birth of Venus typifies the work produced in the academy. In fact, it won the Grand Prix de Rome award when it was exhibited at the academy's annual exhibition, called a Salon, in 1879.

Adolphe-William Bouguereau, The Birth of Venus, Oil on Canvas, 1879

Standing almost ten feet tall and containing twenty-two figures, the painting is undoubtedly impressive. And, more importantly from the perspective of the academy, it follows all the rules. The subject - Venus traveling in her scallop shell to Cyprus - is a Classical one. The style is both illusionistic and idealized, which is exactly the way the academy wanted Venus to be shown.

To get some sense of just how similar all the academic artists were, it is worth looking at another painting of the same subject by one of Bouguereau's contemporaries, Alexandre Cabanel. While it's not the same as Bouguereau's The Birth of Venus, it is profoundly similar.

Alexandre Cabanel, The Birth of Venus, Oil on Canvas, 1863

One might ask who, besides the other members of the academy, was the audience for artists like Bouguereau and Cabanel. One group they appealed to was the Bourgeoisie. Their work sated the Bourgeoisie desire for both a recognizable story (one they already knew from Classical mythology) and an appealing fantasy. Bouguereau's delicate maidens and chubby cherubs were predictably enticing. In other words, Bouguereau's paintings were the pop music of his day - a little bit sexy, very repetitive, always giving the people what the people want.

Adolphe-William Bouguereau, Return of Spring, Oil on Canvas, 1886

Part of the reason the Bourgeoisie were so used to seeing the same kind of art over and over again was the nature of the annual Salon in Paris. For many years it was the only public art exhibition in Paris, so whatever was rejected from the Salon was simply not seen by a wide audience. If the jurors had been interested in showing new and challenging work to the public, such work might have gradually crept into the mainstream, but because they were conservative, most Parisians attending the salons developed a taste for only one kind of art.

As one might expect, not every artist was as eager to follow the rules as Bouguereau was. Some artists went ahead and experimented with new styles, approaches, and subjects. In 1863 the jurors for the annual Salon rejected 3,000 of the 5,000 works submitted. Not only did they reject these works, they actually went so far as to call them "a serious danger for society". In response to this, Emperor Napoleon III ordered that the refused artworks be exhibited in a second show, the Salon des Refuses. One of the best known paintings from the Salon des Refuses is Manet's Luncheon on the Grass.

Edouard Manet, Luncheon on the Grass, Oil on Canvas, 1862-1863

A person unfamiliar with the art being produced in the academy might assume that Luncheon on the Grass was controversial because it contained nudity. In fact, the public was used to seeing nudity in art. What they were not used to seeing was an ordinary women in an ordinary setting without any clothes on. An idealized nude Diana or Venus was acceptable to them, since they had seen it before and it belonged to the world of fantasy. But an average woman looking directly out from the picture frame at the viewer was jarring and new.

Manet became something of a hero to other artists who admired his independence. Many of the Impressionists - Monet, Pissarro, Sisley, Renoir, etc. - counted him a friend and colleague. They broke convention just as he had. Unlike the academic artists before them, they paid more attention to light and color than to carefully rendered form. Like Manet, they paid a price for their courage. Their paintings were initially ridiculed, and Monet suffered in poverty through the 1860's and 70's until the 80's when he was finally established as a success.

Claude Monet, Impression Sunrise, Oil on Canvas, 1872

It's difficult for us today to see how revolutionary Manet, Monet, and their fellow rebels were when they first showed their work. This is largely because of what has been done to the Impressionist paintings. Museum stores sell myriad versions of these paintings printed on every surface imaginable - a Monet on an umbrella, a Cezanne on a coffee mug, a Renoir on a t-shirt. What was once jarring because it had never been seen before is now hardly noticed because it is ubiquitous. Carrying a Monet umbrella is not a countercultural statement. If anything it is a conservative one. And most people, if you ask them, will say that they love Monet, that he is one of the artists they most admire.

It's tempting to draw simplistic conclusions at this point - to say that all of us like things we have seen before and dislike things we have not. I don't think the situation is quite that dire. There always have been and always will be people who are open to what is new and challenging. The trick is to give these new things a chance, to spend enough time with them to see if they have something surprising and delightful to offer us. We need to turn off the most popular songs and listen to the ones we haven't yet discovered. We need to recognize that this is mentally taxing, that it doesn't feel as good as playing the same song over and over again, but that it's ultimately the only way to avoid the situation we have in pop music today, where everything is contentless, shallow, and repetitive.

Everything Which is Yes: E. E. Cummings on Gratitude

I can't remember when I first encountered E. E. Cummings, but I think it was my junior year of high school when I took a creative writing class. His wacky syntax, joyful rhythms, and refusal to play by the usual rules of grammar must have spoken to my teenage taste, because while I was sitting in portable classroom number three I began to love his poems. Later, in college, I remember learning that Cummings was inspired by the principles of Cubism and that the syntactical structures in his poetry echo the visual forms in Cubism. Cummings even made a point of visiting Picasso during one of his many trips to Europe, because he was so enamored with the artist's ideas. I was delighted by the sheer novelty of this concept: a poet appropriating ideas from painting and using them to form his sentences. It seemed like a terribly clever idea and a very good topic for a paper. (Being in college, I had to write one anyway.)

If, back then, I noticed the effusions of gratitude which are also a part of Cummings' work, I don't remember it. Of course Cummings is clever, but he is much more than that. Here he is at his most ebullient:

i thank You God for most this amazing

day:for the leaping greenly spirits of trees

and a blue true dream of sky;and for everything

which is natural which is infinite which is yes

(i who have died am alive again today,

and this is the sun's birthday;this is the birth

day of life and of love and wings:and of the day

great happening illimitably earth)

how should tasting touching hearing seeing

breathing any-lifted from the no

of all nothing-human merely being

doubt unimaginable You?

(now the ears of my ears awake and

now the eyes of my eyes are opened)

e.e. cummings

In one sense the poem is a prayer addressed to God, but in another sense it is also a reminder of what gratitude sometimes looks like. Cummings is not writing about gratitude for health, success, happiness, or money. He is expressing gratitude for merely being, gratitude for every visual, tactile, and auditory sensation which lifts him up out of the "no / of all nothing". Cummings celebrates the very fact that he is alive, or, more specifically, "alive again" (italics mine). It is as though his eyes have been opened to the gift of life, and he cannot get over the extravagance of the gift.

Time is an interesting element in the poem, because Cummings celebrates both beginnings - "the sun's birthday" - and things without end - "everything / which is natural which is infinite which is yes". It is strange to think of the sun as having a birthday, since birthdays are measured by the earth's revolution around the sun. But the sun did come into being at some point, and celebrating that moment is a way of celebrating light, life, warmth, seasons, and time. Infinity may not be measurable, but if it were, we would probably measure it using the sun, since this is the way we measure finite time.

But I'm getting caught up in the cleverness of the poem again, and I don't think that's the most important part of it. What I like best here is the sheer joy and affirmation of being, the "everything which is yes". I found a clip of Cummings himself reading the poem, and when I hear him speak, I sense his own gratitude in each slowly-savored syllable.

Outdoors right now there are very few "leaping greenly spirits of trees". Those greenly spirits turned yellow and red a month ago; now many of them are bare. Even the "blue true dream of a sky" is darkening earlier, and tomorrow morning we will have to turn back our clocks to save the daylight. Still, Cummings' poem feels appropriate to this season. Being alive to every sensation - even the bitter winds that indicate winter is coming - is a gift.

While Cummings may have first appealed to me for his syntactical dexterity, I'm realizing now that his gifts as an artist extend far beyond phonetic gymnastics. I suspect this is the case with many of the best writers and artists. They draw us in by delighting or surprising us and then, while our guard is down, tell us something terribly important. Arguably, this is one of the tasks that is set before artists: find a new way to show the truth, and people who dismissed it the first time around may listen to it in this novel form.

When A Book Was Costly

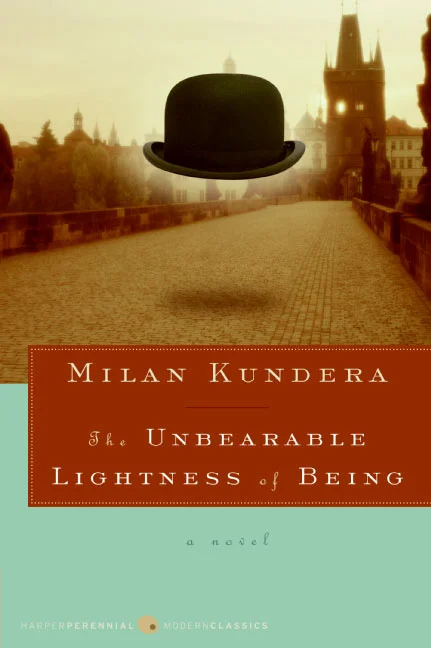

A couple weeks ago I went to the AAUW book sale in Holland, Michigan. The sale is held in the Holland Civic Center where the old gymnasium is lined with folding tables stacked high with used books organized according to genre. If you show up Saturday morning, you can buy any book you like for one dollar. By Saturday afternoon, a whole grocery bag full of books is only five dollars. For bibliophiles on a budget, it's like Christmas morning.

One of my purchases this year was a worn copy of The Golden Age: Manuscript painting at the time of Jean, Duke of Berry by Marcel Thomas. The lavishly illustrated 14th and 15th century manuscripts shown in the book were originally commissioned by kings, princes and nobleman. Filled with intricate, handmade, gold-illuminated illustrations, these books were all terribly expensive. A library full of them was a true status symbol, and the Duke of Berry had just such a library.

Most of the illuminators - the people who illustrated the books - were anonymous. Some of them, of course, were monks, but others were men (and occasionally women) who were hired to do the work. We don't know a lot about the lives of these illustrators-for-hire, but we do know that their position was not an esteemed one. They were merely workmen who had to keep their clients happy in order to hang on to their jobs. That so few of them signed their work is not surprising since it hardly constituted a creative expression on their part. In fact, some of the designs in the manuscripts were made by multiple artists - one who painted the marginalia (the borders), one who painted the background, and another who painted the main figures.

Still, a few artists were known by name, particularly the three Limbourg Brothers, who were hired by Jean, the Duke of Berry, to create a book of hours - a book used for reciting prayers. I've admired the work of these brothers before, and as I flipped through my new book, I came across stunningly beautiful images of their work - a painting of naked Eve dangling the forbidden fruit in front of Adam and a painting of a young, aristocratic woman about to be betrothed to her husband in the verdant month of April. And yet, as masterful as the images might be and as much as I love the Limbourg Brothers' work, I had a hard time slowing down enough to focus on any one image. Like the Duke of Berry, I have many, many books. In fact, I have access to far more books than he did. So how do I slow down enough to look at one image when I have access to so many?

Limbourg Brothers, The Tres Riches Heures of Jean De Berry, The Temptation and the Fall, Ink on vellum, 1413-1416

Limbourg Brothers, The Tres Riches Heures of Jean De Berry, Calendar: The Month of April, Ink on vellum, 1413-1416

This, I think, is the challenge of being a reader today. Far from struggling to afford reading material, most of us cannot get away from things demanding to be read, looked at, consumed.

Which reminds me of a painting by the contemporary artist Vincent Desiderio. It's called Cockaigne, which is a reference to a much earlier painting by Pieter Bruegel, called The Land of Cockaigne. Both paintings are about gluttony. Bruegel's is about a mythical land where people have more than enough to eat and thus eat far too much. Desiderio's is about an all-too-real place, the place we all live in, where we can gorge ourselves on imagery.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Land of Cockaigne, Oil on panel, 1567.

Vincent Desiderio, Cockaigne, 1993-2003

The images on the pages of the books in Desiderio's painting are famous - miniature images of paintings by Vermeer, Matisse, Masaccio and others. As viewers, we struggle to take them all in and find ourselves, like the men in Bruegel's painting, intoxicated by the overabundance. Part of what Desiderio is communicating here is the challenge of being an artist today: when the culture is already saturated with more images than anyone can possibly take in, how do you manage to make your artistic voice heard? How do you choose an artistic language, when you could draw inspiration from any one of these many artists?

Contrasted with that of the medieval illuminators, our position as painters today is truly strange. They knew exactly what they were supposed to do - make an illustration that would please their patron. We are not always sure what to paint, and many of us couldn't say who exactly (if anyone) we are trying to please. They didn't even bother to sign their names to their work. We aggressively brand and promote ourselves. They had limited artistic influences and worked in a style similar to that of their peers. We have almost unlimited access to the art of other cultures, places, and times, and we try to be unique.

None of this, of course, is going to change soon. We can't return to the age of handwritten books, and we shouldn't romanticize it. And yet, every once in awhile I find it necessary to take a short break from the visual feast that is our culture, to stare out at nature or close my eyes until I have built up an appetite again, and then slowly, quietly, look at one image and try to see it with something resembling fresh eyes.