A Human Crisis

“There’s no refugee crisis, but only human crisis... In dealing with refugees we’ve lost our very basic values.”

The expansive, white spaces of the Trade Fair Palace in Prague, currently a gallery for the country’s vast modern art collection, were once used as an assembly point for Jews before their deportation to Terezin concentration camp. From there, they were often sent to Auschwitz and other extermination camps. The site is a place of ghastly horror and glorious achievement, impending annihilation and avant-garde boldness, obvious cruelty and enigmatic artistry. To take in this paradox is too much for most visitors. I, like many other museum-goers, began my visit to the site with a creamy cappuccino and a sliver of spicy, hazelnut cake at the cafe before heading cheerfully into the galleries, my conscience not yet clouded by thoughts of those who had come there under other circumstances.

Ai Wei Wei’s exhibition Law of the Journey, currently on view , demands that visitors to the museum do more than enjoy a pleasant day amongst beautiful pieces of art. He takes on the topic of the current refugee crisis, or as he describes it “human crisis”, and brings the viewer viscerally close to the reality of being not just homeless but stateless. The issues he addresses are contemporary, but his work strikes just a bit harder in this historically charged space. Who can stand in these halls and say, “But it would never happen here!”

Filling the gallery space is a larger-than-life, black, inflatable raft with more than three hundred inflatable figures. Hung at an angle, the raft seems to be cresting a wave, and the undulating movement of riding across the sea in a thin plastic boat, with all the nausea and fear that must accompany such an experience, is palpable. The sense of alienation and claustrophobia is unmistakable as well, and each of the figures looks just like the others, all crammed together like cattle in an industrial farm. On the ground outside of the boat, a few lonely figures drift in their inner tubes, their giant cartoon-like hands reaching up to the viewer’s eye level.

Beneath the raft, there is enough space for visitors to walk, and on the floor under the raft, there are printed quotes from many, seemingly disparate, authors. Some, like Vaclav Havel and Franz Kafka, are from Prague, but others, like Saint Augustine, are not. In fact, the quotes are drawn from a very wide range of cultures and eras, as if Wei Wei had dipped his hand into the waters of collective, universal wisdom and pulled out whatever came to him. Here are a few examples:

“The tragedy of modern man is not that he knows less and less about the meaning of his own life, but that it bothers him less and less.”

“Since you cannot do good to all, you are to pay special attention to those who, by the accidents of time, or place, or circumstances, are brought into closer connection with you.”

“the train derails,

the ship sinks

the plane crashes.

The map is drawn on ice.

But if I could

begin this journey all over again,

I would.”

Depending upon which quote I was looking at in a given moment, my thoughts about the raft installation shifted. While reading Hikmet, I thought of how refugees have so much to gain by leaving their native countries that they are willing risk all types of disaster; while reading Augustine, I thought of how I might someday have the opportunity to help just one refugee; while reading Havel, I thought of how infrequently I pause to consider what work it is that I personally am responsible for doing. What was true for all the quotes, however, was that they nudged me toward a stance of responsibility and action. I couldn’t stand there under that boat looking at these words and say that none of it was my problem.

On the walls of the gallery space there were rows and rows of tiny photographs of refugees. In contrast to the large, anonymous black figures in the center, they were frightfully specific. A woman wrapped in a foil blanket, a child gripping a man’s shoulder, a man with orange sneakers stepping out of a small raft and into ankle-deep water - these were, and are, real people.

Artwork with a clear political message sometimes comes across as emotionally manipulative or propagandistic, but Wei Wei’s work hit me less with a message and more with a question. Could I walk under the shadow of that inflatable raft without imagining the depth and cold of the ocean? Could I scan a wall papered with photographs of huddled masses with the same boredom and indifference I have toward my Instagram feed? Did it matter that the same space where I’d just enjoyed cake and coffee once spelled terror and destruction for the Jewish families who entered it? Or, to borrow a question from a Kafka quote included in the installation:

“We are as forlorn as children lost in the woods. When you stand in front of me and look at me, what do you know of the griefs that are in me and what do I know of yours.”

Living Memorials in the Kingdom of Forgetting

My mother and I felt unsteady climbing the unnaturally large stairs leading up to The Memorial to the Victims of Communism in Prague. The flat portions of the stairs were slanted slightly downward, so, to avoid slipping, I decided to walk sideways. Once I’d turned, I found myself looking directly at the bronze strip of text running down the center of the stairs. I couldn’t read the Czech words, but later I found out they were a list of estimated numbers for those affected by Communism.

- 205,486 arrested

- 170,938 forced into exile

- 4,500 died in prison

- 327 shot trying to escape

- 248 executed

Sculptor: Olbram Zoubek, Architects: Jan Kerel and Zdeněk Holzel, Memorial to the Victims of Communism, 2002

Even before I knew what the words meant, I could already sense the gravity of the memorial, since the sculptural aspect of it was unmistakably a representation of suffering. Like automatons falling into formation, seven, identical, bronze figures descend the staircase. Naked, thin, and hollow, the men look like broken shells of human beings. The one at the front is whole, but each figure behind him looks increasingly less human since portions of their bodies appear to have been torn away. At the back of the line is a single, narrow, abstracted foot form. Seen apart from the others, it might not even be identifiable. The largeness of the stairs added to the overall effect, since the task of approaching the figures was itself arduous, and something of their exhaustion had crept into my own body by the time I got to the top.

Sculptor: Olbram Zoubek, Architects: Jan Kerel and Zdeněk Holzel, Memorial to the Victims of Communism, 2002

A couple weeks before the trip I listened to an interview on the podcast On Being with Dr. Bessel van der Kolk, a psychiatrist in Boston who works with survivors of trauma. Dr. van der Kolk spoke of a conversation he had early on in his career with a man who had survived the Vietnam War only to be frequently woken by terrible nightmares after his return home. He prescribed him medication for the nightmares but discovered later that his patient wasn’t taking the medication. When he asked him why not, the patient said something which touched him deeply. He said, “I did not take your medicines because I realized I need to have my nightmares, because I need to be a living memorial to my friends who died in Vietnam.”

This burden, that of living as a memorial to the dead, is not unique to that veteran. There are people in every community who continue to suffer because of what they lived through in the past, and while their nightmares are their own, we all bear some responsibility to remember the past. Walking the streets of Prague, I wondered how many of the people I saw could have told me stories about their lives during communism. Did the women my age, who were four years old when communism ended, remember it at all? What would the women my mother’s age, most of whom spoke Czech and Russian (but not English), have told us if we could have spoken to them in a language they understood?

Preserving memories is an inherently powerful act, since it allows the past to inform the type of future we want to create. When living under an oppressive government, it is also a subversive act, since it means the government doesn’t have exclusive rights to the peoples’ stories and self-understanding. Perhaps it is not surprising, then, that the period after 1968 in Czechoslovakia has become known as the "era of forgetting". In the spring of 1968, Czechoslovakia’s leader Alexander Dubček attempted to reform his country’s communism, and he loosened the restrictions on travel and speech. The Soviets, however, were not pleased with these changes, and in August of that year Warsaw Pact allies invaded Czechoslovakia and began a process of “normalization”, in which the reforms were reversed and history was rewritten. Soon, the country became known as the “Kingdom of Forgetting”, since there was a concerted effort to erase aspects of Czech national identity and communal memory which would have made Soviet rule more abhorrent to the people than it already was.

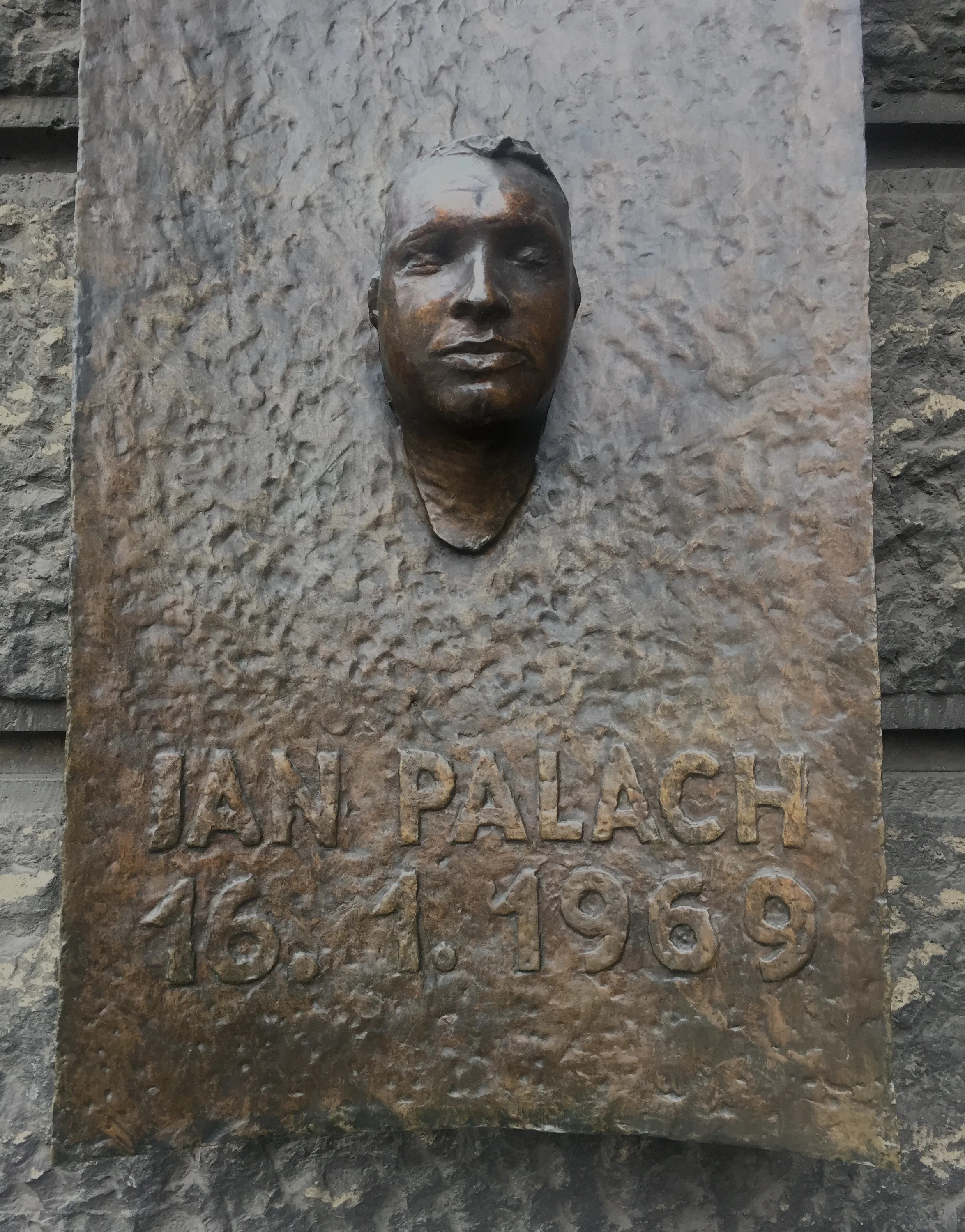

It was in this climate in 1969 that Jan Palach, a student at Charles University in Prague, made the decision to set his own body on fire and die in protest of the way people had given in to the invasion. His act might seem futile, but his goal – to spur his countrymen on to resist the Soviets – was admirable, and his courage was undeniable. Hundreds of thousands of Czechs attended his funeral, and they, the people who acknowledged what he had done, became the living memorials to his sacrifice. For these people, Palach’s grave in Prague was a pilgrimage site. Not surprisingly, the secret police pressured his family into exhuming the body and cremating it, so that the grave, such a powerful threat to their kingdom of forgetting, would cease to exist.

Today, twenty-eight years after the end of communism in Prague, there is a lasting memorial to Jan Palach’s sacrifice in the place where his burning body fell to the ground. The cobbled pavement there in Wenceslaus square swells into two mounds – one for him and one for another young man, Jan Zajíc, who also set himself on fire in defiance of Soviet oppression. Connecting the two mounds is a bronze cross. On the day we visited the site, there were also flowers and candles on the site. It was an ordinary Tuesday, so I can only imagine how many more flowers we might have seen if we had visited on the anniversary of his death.

Memorial to Jan Palach and Jan Zajíc in Wenceslaus Square

On our last day in Prague we went to see one final memorial, the death mask of Jan Palach, which is on the façade of Charles University’s Faculty of Philosophy where he once studied history. Both his youth and his burn wounds are evident in the mask, so it is hard not to cringe while looking at it. Still, the place is primarily a lively one. Outside the building, a few students lit up cigarettes in the chilly March air. Inside, others clustered in small groups chatting or sat at small tables with their books. And on the stairs, one leapt effortlessly upward, headed toward class and a future where he and his classmates will carry the responsibility of remembering their country’s past.

Jan Palach's death mask taken by Olbram Zoubek

Disorder and Decorum: Breaking the Rules at the MFA

Parallel exhibits, Beyond Limits and Political Intent, currently share the Henry and Lois Foster Gallery at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Selected from the museum's collection, the work in these shows represents a diversity of media. From bold, red screen prints by Andy Warhol to an airy, white installation by Ernesto Neto, there is not one style on display here, but many. The unifying factor in the shows is not an aesthetic but the way these artists provoke us to question where we stand, both where our physical bodies exist and where we stand ideologically on social issues.

Andy Warhol, Red Disaster, 1963, 1985, Silkscreen on canvas, two panels.

When I made the decision to go see the work, I had imagined myself walking quietly through the gallery, pausing now and then to read a description or write something down. To my surprise and chagrin, the museum was also hosting a free event for the Lunar New Year, so the building was pulsating with the energy of children, parents, babies in strollers, and guards anxious to protect the valuable works on display. More than once I heard a "No!" and jerked my head around to see a museum employee striding over toward a miscreant child. Those alarms, which usually go off when an inquisitive guest leans in too closely, had become a chorus of unheeded caution as tiny museum-goers pranced around the work, stepping over lines and reaching out to touch things. At one point, I stood still for what was apparently long enough to arouse suspicion and a guard, set on edge by the general atmosphere, approached me, rather aggressively, to ask, "What are you looking for?"

A couple hundred juice boxes and slices of cheese pizza were in order. Sadly, the cafeteria on the garden level was closed, so people had formed a long line outside the little cafe by the bookstore. I, too, had planned on eating something, but seeing the slowness of the line and the general din surrounding the area, I decided to walk down to the empty, foodless, and blissfully quiet cafeteria space where I ate the Payday candy bar I keep in my purse for such occasions.

Strengthened, I returned to the gallery and resolved to see it for what it was: an important, albeit raucous, pair of exhibits. In the first show, Political Intent, a series of Kara Walker's silhouettes stretched across a dark gray wall. Narratively ambiguous, her work shows happy domesticity and sexual violence coexisting as black and white human shapes intertwine. Walker draws on the nineteenth-century, American tradition of decorating one's home with sweet, innocent cut-paper silhouettes, but her work acknowledges the ugly side of that era and forces us to stop prettifying the truth of the African American experience. There's something physically discomforting about her work, since it both reduces the bodies of human beings into flat stereotypes and, also, simultaneously, draws attention to the violation of those bodies.

Kara Walker, The Rich Soil Down There, 2002, Cut paper and adhesive on painted wall

Adjacent to Walker's work, there was a video, Melons (At a Loss), by Patty Chang in which she cut into her blouse with a knife to expose a large melon in the place of her breast. She proceeded to scoop out the contents of the melon and place them on a plate. Calling women's breasts melons is both vulgar and cliché, but the video was neither. It was cringe-inducing, but mainly because of the sharp knife and the strangeness of seeing someone remove what appeared to be the contents of her own body.

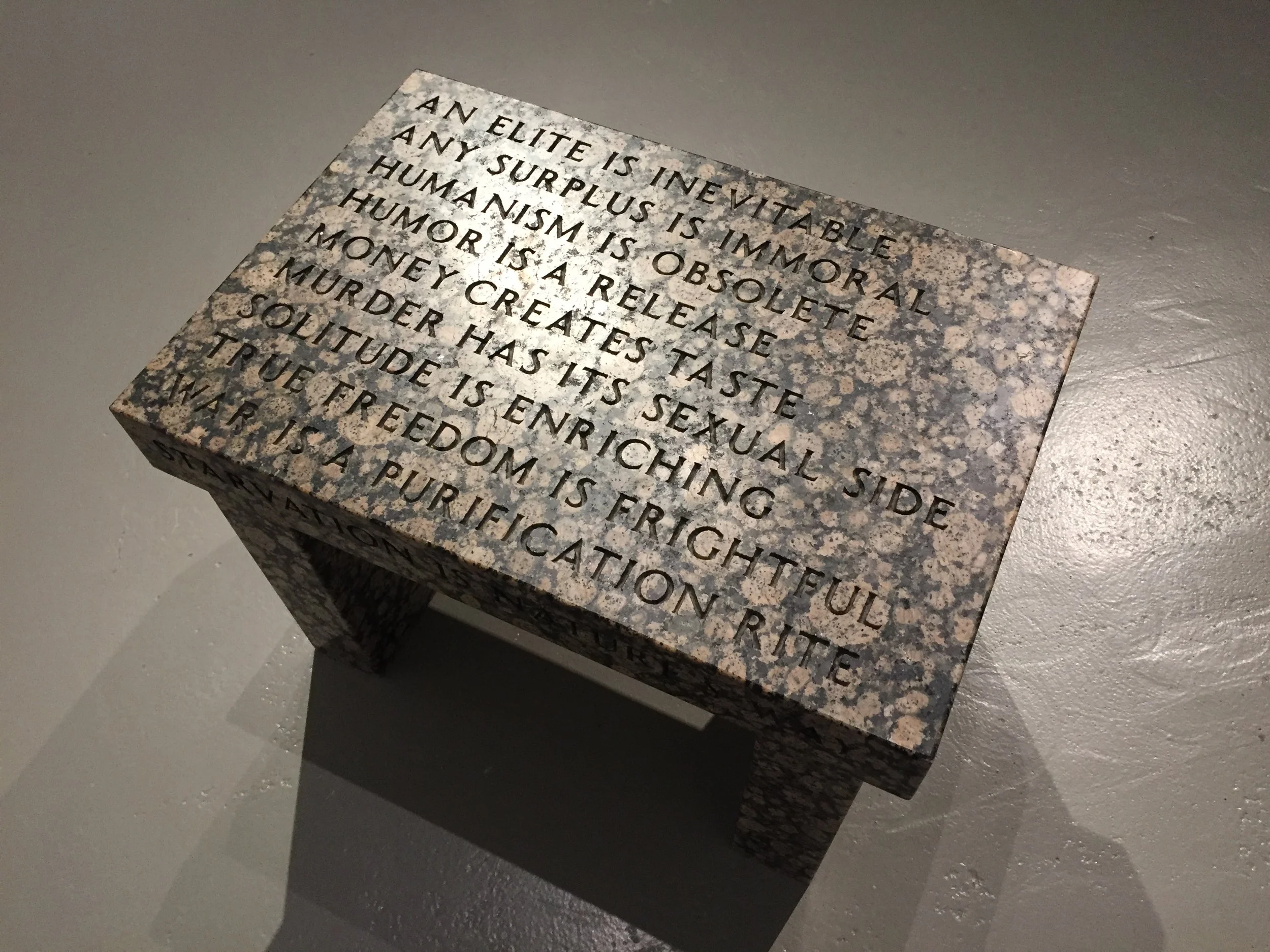

Jenny Holzer's Truism Footstool was also part of Political Intent. It was inscribed with truisms, including, "An elite is inevitable." and "Any surplus is immoral." The sign near the stool said to sit on it, but it was too low to be comfortable. I began to wonder whether the seat was meant to lift people up or bring them down. A footstool, after all, is often used for reaching high things, and the piece could be interpreted as a symbol of the foundation many power-seekers build their careers upon. Either way, the pedestrian way the truisms were stacked one on top of another made them seem meaningless and crass, and using the stool made me feel complicit with the statements.

Jenny Holzer, Truism Footstool, 1988, Baltic brown granite

Moving across the hall to Beyond Limits, I encountered Mona Hatoum's Grater Divide. The larger-than-life cheese grater with its human scale and sharp blades looked more like an instrument of torture than a cooking utensil, and, though I knew the artwork was not dangerous, I gave it a wide berth as I walked around it. As its title indicates, the piece is about division, and it functions as a screen between the two exhibits. The piece is also about Hatoum's experience as an exile from Lebanon during its civil war. War makes the ordinary things of home into something ghastly and strange, just as she does with this enlarged grater.

Mona Hatoum, Grater Divide, 2002, Patinated mild steel

In the next room, I walked under Ernesto Neto's Prisma Branco, a latticework of drooping, biomorphic forms. Both heavy and light, the large installation hangs pendulously from the ceiling but cannot possibly weigh more than ten or fifteen pounds, seeing as it is made from thin, nylon fabric. The pink and blue tendrils hung at about the height of my eyes, and while I resisted the urge to reach out and grab one, many of the children in the space did not. In the description of the work on a nearby wall, I read that the pink and blue forms were meant to symbolize the fundamental, biological connections between human beings, and it did seem that the piece exerted a force pulling people together under it.

Ernesto Neto, Prisma Branco, 2008, Polyamide nylon and glass beads

Another piece in Beyond Limits, Yoan Capote's Abstinencia (politics), shows a set of cast bronze hands that spell out the word politics in sign language. He made the casts from the hands of many individual Cubans who feared openly discussing issues in their country, so the piece represents discreet, collective resistance. Modest in scale and subtler in its message, the piece fit the theme of the exhibit but spoke using a silent language.

Yoan Capote, Abstinencia (politica), 2011, Cast bronze and unique reproduction made from original watercolor print

Though they exist within the lofty halls of a museum, the works in these shows are not meant purely for aesthetic contemplation. Perhaps it is just as well that I visited on a day when peaceful reflection was out of the question. The crowds of fussy, hungry children and tired parents were not unlike those I had seen at the Women's March in Boston just two weeks ago, and I was reminded that political engagement is not tidy, easy work. I wonder, in fact, if some of the artists in the shows would have been happy to see kids transgressing the norms of museum behavior since their art is not meant to exist within the confines of society's expectations. In that sense, the loss of decorum was appropriate, and while I still hope to eat a nice salad and relax the next time I visit, I'm glad yesterday was a disorderly day at the museum.

Theater Troupe vs. Army

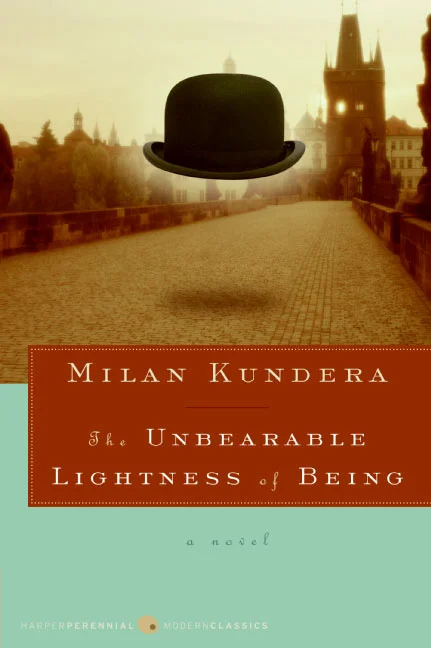

“There is no means of testing which decision is better, because there is no basis for comparison. We live everything as it comes, without warning, like an actor going on cold.”

Milan Kundera’s novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being explores the idea that each of us can choose only one of the many possible paths for our lives. Since we only get to live our lives once, we do not know what our lives might have been had we chosen otherwise. We only know what our lives are now as a result of the choices we really have made. The main characters in the book are Tomas, a philandering doctor, and his wife Tereza, a sensitive bibliophile and photographer who is utterly devoted to him. The two of them meet through a series of unlikely coincidences, and one of the central choices in the novel is Tomas’ choice to marry Tereza, a decision that heavily altered the course of his life.

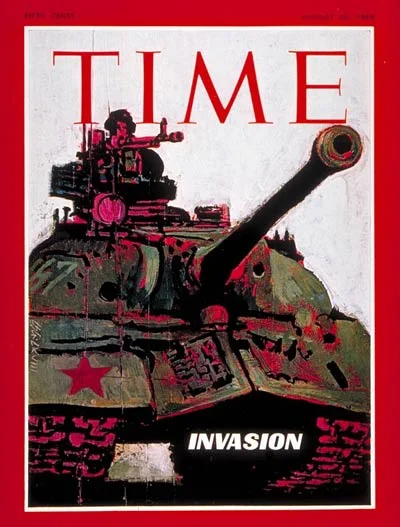

Tomas’ and Tereza’s relationship is played out against the events of 1968 in Prague, so the Soviet invasion in August of that year and the subsequent reestablishment of the Communist regime play heavily into the plot. In particular, the regime’s restriction on freedom of expression is an important part of the story since early on in the book Tomas writes an article for a Czech paper condemning Czech communists.

1968 Cover of Time Magazine

Fearing recrimination for the article he wrote, Tomas, along with Tereza, flees to Switzerland, where Sabine (Tomas’ longtime mistress) is already living. Tomas is happy enough in Zurich, but Tereza struggles to find meaningful work. Tereza is also acutely aware of the fact that Tomas continues having affairs with multiple women, including Sabine.

Feeling that she is a burden to Tomas, Tereza makes the decision to move back to Prague without telling him. It is a strange decision since her devotion to him is absolute, but it makes sense when seen in the context of her fear that she is ruining his life. Tereza tells herself that “in spite of their love, they had made each other’s life a hell." What she doesn’t know as she is making this decision is that as soon as Franz discovers she has left Zurich for Prague, he will leave to go be with her. And, of course, once he is back in Prague, he will be faced with the consequences of what he wrote about Czech communists.

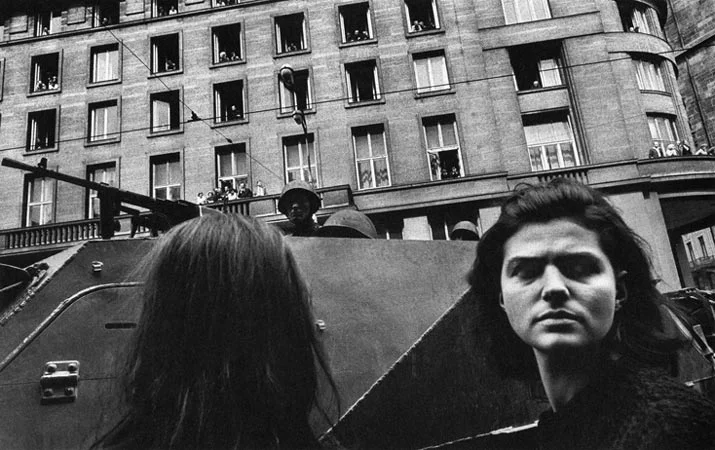

Josef Koudelka, Prague, August, 1968, Digital Inkjet Print

In a book where the choice to do one thing instead of another is a central theme, this choice stands out as one of the most consequential. Once in Prague, Tomas faces pressure to denounce his anti-communist article. He refuses, loses his position as a doctor, and becomes a window washer instead. Still, even after all of this, it is not the end of his being pressured to sign documents others have written. Soon an editor of an underground paper approaches him about signing a petition for the amnesty of political prisoners. Tomas, however, feels that he is being manipulated once again, just by a different group of people, and refuses to sign.

Meanwhile, Franz, an unhappily married intellectual from Geneva, falls in love with Sabine, and the two of them travel together whenever he has to lecture in a foreign city. Temperamentally similar to the ever-committed Tereza, Franz cannot tolerate being with two women at the same time, and ultimately leaves his wife for Sabine. Unfortunately, Sabine hates to commit and she leaves Franz when she realizes he wants to marry her.

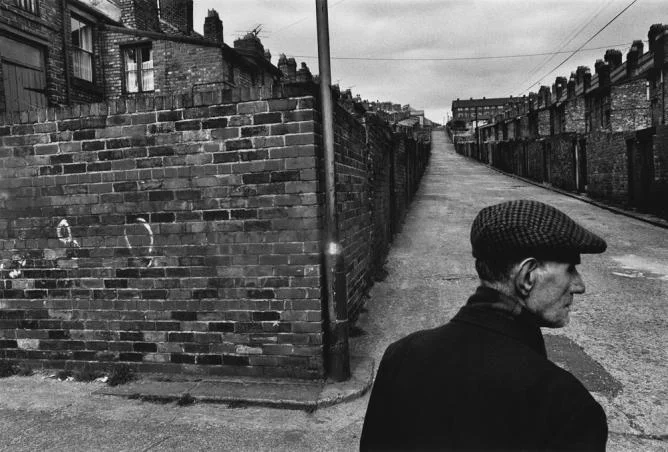

Josef Koudelka, From Exiles - Revised and Expanded Edition,

Though Franz finds another lover, he never fully recovers from the loss of Sabine, and many of his later decisions are influenced by his enduring attachment to her. When he receives word from a colleague of a plan to march on Cambodia and demand permission to enter the country with medicine and food, he thinks of what Sabine might have wanted. Remembering that she was a refugee from another country occupied by its neighbor’s Communist army, he imagines she would want him to march on Cambodia, and he agrees to participate.

From time to time Kundera breaks from the narrative and interjects his own authorial thoughts about the situations his characters find themselves in. In analyzing Franz’ decision to march in Cambodia, he makes a comparison to the editor in Prague who encouraged Tomas to sign the petition.

“I can’t help thinking about the editor in Prague who organized the petition for the amnesty of political prisoners. He knew perfectly well that his petition would not help the prisoners. His true goal was not to free the prisoners; it was to show that people without fear still exist. That, too, was playacting. But he had no other possibility. His choice was not between playacting and action. His choice was between playacting and no action at all. There are situations in which people are condemned to playact. Their struggle with mute power (the mute power across the river, a police transmogrified into mute microphones in the wall) is the struggle of a theater company that has attacked an army.”

A theater company cannot, at least not with brute force, defeat an army. And yet, when faced with the choice between doing nothing and playacting, playacting becomes a more appealing option. Writing a letter which will not have its desired effect, acting out a drama which will not bring about change, signing a petition whose goals will not be achieved, or doing absolutely nothing – these are the sorts of choices people living under repressive regimes have to choose among.

The characters in this book are continually making choices. Whether it is signing a marriage certificate, a petition, or a letter to the editor, the question is always, “Is it worth it?” Will the outcome of signing be better than the outcome of not signing? And along with these questions is the ever-present question of, “How can we know that we chose well since we will never know what else might have been?” If Tomas had never met Tereza, he might have had a successful career as a doctor in Zurich. Would this outcome have been better than the life he lived by her side?

At the end of the book, this question is still not fully resolved, but the fact of the book’s existence points toward an answer. After all, Milan Kundera wrote the book. You cannot write a book without believing in the power of words and in the power of creating things. Perhaps there are times when artists, writers, and actors look like theater troupes waging war on real armies. Perhaps the choice to commit to something, whether it is a movement or a person, appears ineffectual. Perhaps we’ll never know with utter certainty whether the choices we make and the things we create are the right ones and whether they are better than the choices and things we didn’t make. Nevertheless, like Kundera himself, we do choose to make things. We do choose to commit to people and ideas. The very fact that oppressive regimes forbid these things is evidence of their power, so we continue, often in the face of uncertainty, with the work we have chosen.

Josef Koudelka, Bohemia, 1967, Gelatin Silver Print

Note: All the photos in this post are by Czech photographer Josef Koudelka. Koudelka captured many powerful images in Prague during the same period that Kundera wrote about. I have included these photos of real people, since they fit with the general tenor of Kundera's fictional novel.