Telling All the Truth

“Is the painting realistic?” When I hear this question, I know what people mean. They usually want to know if the painting looks like a perfect copy of the thing it represents. The question is a fair one, but sometimes people follow it up with a judgment. “I’m impressed with things that look real – like a photograph – nothing ‘off’.” I even had a stranger walk by my easel once when I was painting outdoors and interrupt me to say that I hadn’t painted the clouds “as they were in real life.” Never mind the fact that clouds are constantly changing... even if they were static, would the goal of the artist be perfect replication?

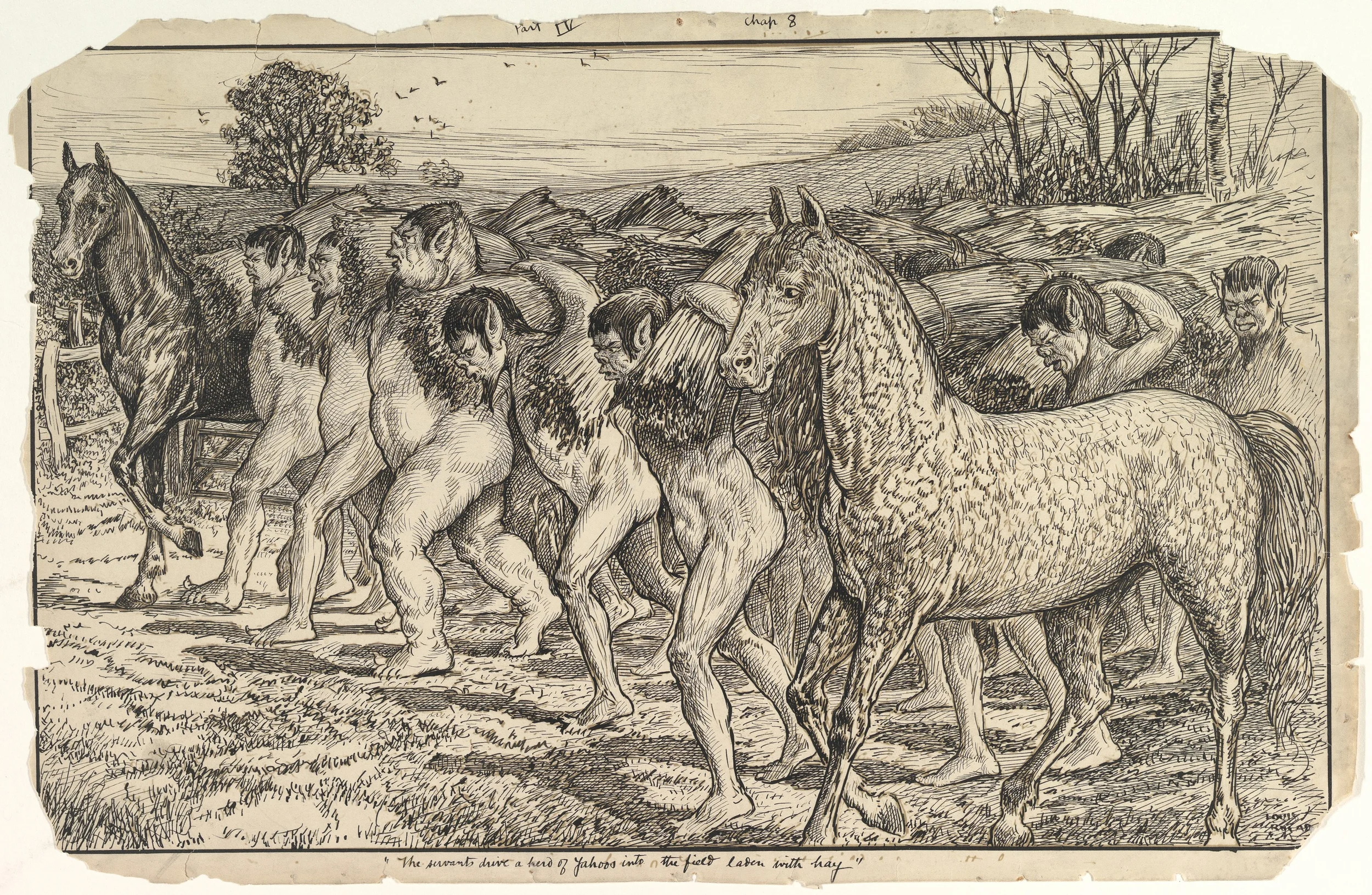

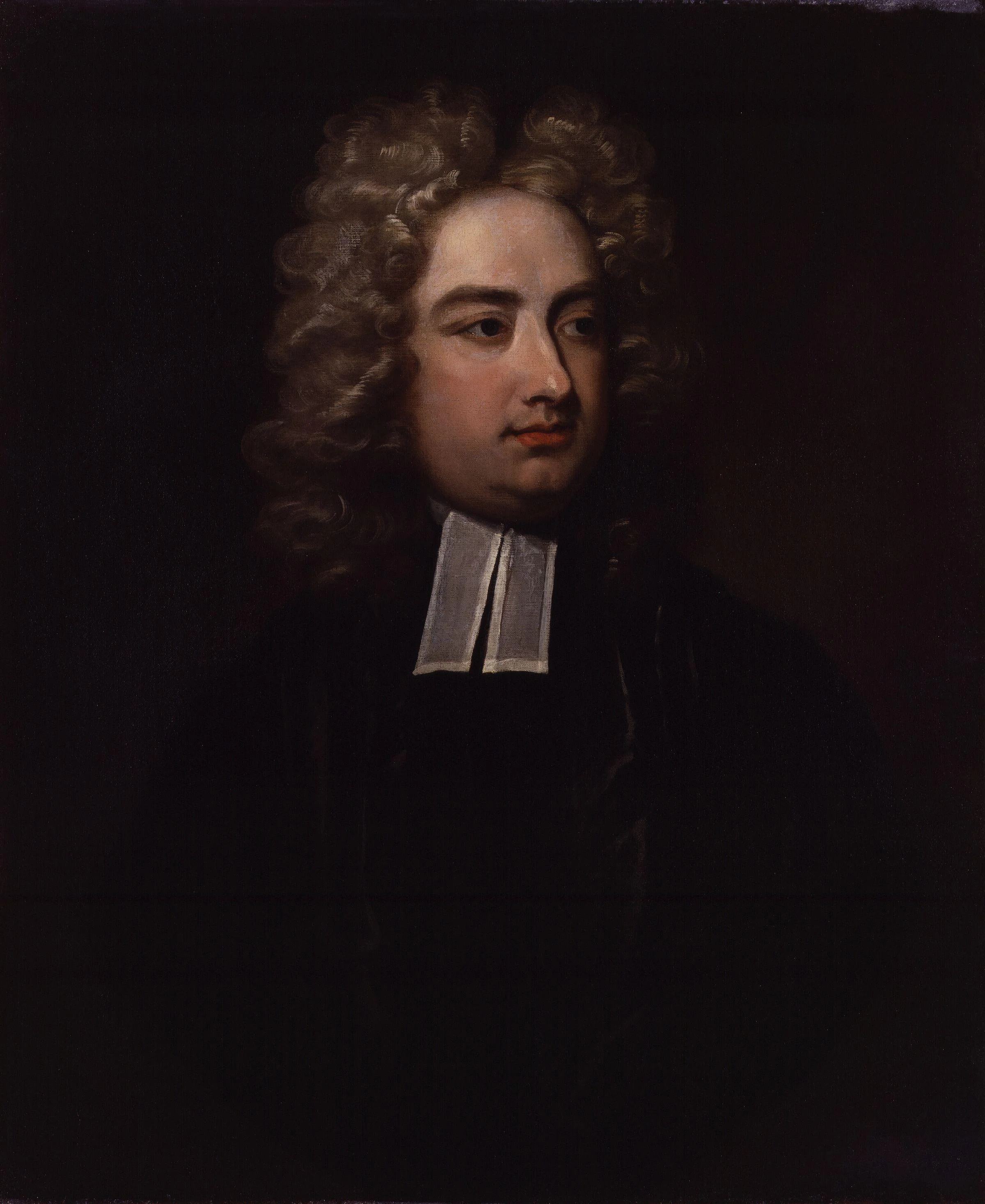

It isn’t hard to recall examples of artists and writers who played with reality. The writer Jonathan Swift comes to mind. In his most famous novel, Gulliver’s Travels, he takes the reader through multiple fictive lands each populated by fantastical characters such as six-inch tall men, sixty-foot tall men, ineffective academicians, and talking horses. (It does seem that one of those four is less absurd than the other three…) Swift’s book exposed the darker side of human nature, and as Gulliver traveled through these varied lands he became increasingly hardened to the reality of how badly human beings sometimes behave. At the end, when he finally arrived in the land of the talking horses, called Houyhnhnms, he preferred the horses to the human-like creatures living there, called Yahoos.

Louis John Rhead, The Servants Drive a Herd of Yahoos into the Field, late 19th - early 20th century, Pen and ink

Swift has been quoted as saying, “Vision is the art of seeing what is invisible to others.” This quote could be interpreted in more than one way. The most obvious is that Swift saw visions of fictional lands in his mind, lands that were invisible to others. More likely, however, the vision he was talking about was his pessimistic vision of humanity. His fictional tales illuminate aspects of human nature that are real but not always apparent.

Charles Jervas, Jonathan Swift, 1710, Oil on canvas

When I read Gulliver’s Travels in college, I learned that it was an example of verisimilitude since it has the semblance of truth. As bizarre as Gulliver’s journey was, it felt real enough to me as a reader that I was willing to ride along and see what would happen next. I “believed” in the realistic details of the story enough that I didn’t object to the completely far-fetched aspects of it. My willingness to set aside my incredulity allowed me to see the larger truth of Swift’s work.

A similar effect plays out in the visual arts. Pablo Picasso’s distorted and fractured forms are almost exactly the opposite what many people would call realistic painting, but he was not unconcerned with the truthfulness of his work. The following is one of his most famous quotes:

“We all know that Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand. The artist must know the manner whereby to convince others of the truthfulness of his lies.”

Like Swift, Picasso used something other than literal representation to show his audience the truth. His paintings are not photorealistic, but they point us toward a real understanding of the things they depict.

Pablo Picasso, Three Musicians, 1921, Oil on canvas

The arts often startle us into a new perspective, a new slant some might say. And yes, I’m talking about Emily Dickinson, who couldn’t go unmentioned here since she is known for writing that we should, "tell all the truth, but tell it slant." I can’t say anything better than she did, so I’ll go ahead and include the entire poem.

“Tell all the Truth but tell it slant –

Success in Circuit lies

Too bright for our infirm Delight

The Truth’s superb surprise

As Lightening to the Children eased

With explanation kind

The Truth must dazzle gradually

Or every man be blind –”

According to Dickinson, part of the reason the truth must be told in slanted and circuitous ways is that the whole of it, the entire blazing, fearsome truth, is too much for us to take in at once. The truth she is writing about here is not the simple, literal truth of making a cloud in the sky look just like a photograph of a cloud in the sky but the complex truth of showing what a cloud (or anything else for that matter) truly is. Capturing the truth of what something truly is at its core is terribly difficult work, and it is far more difficult than merely copying the outward appearance of things. Nevertheless, the paintings and books I most admire are the ones that give me a glimpse - a quick, dazzling flash – of reality.

The Art of Being Alone

New York Magazine recently ran an article titled How to Spend Time Alone, in which a collection of writers muse about the pleasure of solitude in the midst of Manhattan’s masses. As rare as it is for anyone to be physically alone in New York City, it is still possible to feel alone on the subway or when asking for a table for one. In fact, perhaps because of the city’s crowds, these moments of perceived solitude are simultaneously delicious and awkward. No one wants to look like they are alone, but most people need time away from others in order to decompress and think.

The article contains some ideas about where to find this time alone: wear headphones so that no one talks to you, check into a hotel, go to a bar when it is too early for most people to drink, head up to the top of the Empire State Building at 2:00 a.m., etc.

Almost alone at the UICA Theater in Grand Rapids

Most of the ideas are things I could have thought of on my own, but what I find interesting is the fact that there are enough people seeking a break from the frenzy of togetherness (without the embarrassment of being seen alone) to justify such an article.

The cliché of the loner artist is a tired one, and many artists don’t fit neatly into it, but this craving for solitude is especially common among creative people. Ideas need a gestation period in order to develop fully, and the womb-like safety of isolation allows for that growth. The many talented writers and artists who withdrew from society (Thoreau, Dickinson, Van Gogh, etc.) are evidence for this, as are the many artists who wrote about the value of solitude. Picasso is often quoted as saying, “Without great solitude, no serious work is possible.” And, indeed, it is hard to imagine a large committee coming up with the principles of cubism and voting to put them into action.*

Pablo Picasso, Girl Before a Mirror, 1932, Oil on canvas

Pablo Picasso, La Lecture, 1932, Oil on canvas

As the article in New York Magazine makes clear, however, there is stigma in being seen alone. The loner artist cliché is romantic, in theory, but few of us actually want to be mistaken for one of these rarefied hermits. Two of the writers for the magazine, identical twins and collaborative artists Kirk Mueller and Nate Mueller, wrote their own separate accounts (the full versions of which are available here) of the experience of eating alone in a restaurant, something they had never done before. Kirk’s account is telling in that his experience made him anxious at first but then, as he sat there alone, he began to think creatively. He wrote:

“The place was completely full, so I sat at the bar; I don’t think I would like sitting alone at a table, which feels very much like you’re waiting for someone else to come. I asked for kimchee ramen with chicken, and as I sat there waiting for my food to come, I realized I had to entertain myself. So I took out my phone and started skimming an article until it struck me that it looks weird to be alone at the bar on your phone; it felt like people were watching me. So I put the phone away and started people-watching myself, focusing on all these minute details. I made up stories about the people I saw eating, and I’d look at people on dates and watch their micro-expressions, the way they laughed at jokes. (Is the one person more into it than the other?) It was fun, and I ended up staying for about 45 minutes.

When the check came, I realized that nobody was judging me for eating ramen alone. Everyone’s wrapped up in their own lives. And I actually enjoyed being in the moment and noticing things I had never noticed before. I definitely would like to do it again – maybe a couple of times a year.”

Once Mueller put away his phone and started looking around, his next impulse was to begin creating stories about the people around him. Maybe this isn’t surprising; Mueller is already an artist and presumably a naturally creative person. He and his brother are creative in almost every aspect of their lives. But would he have come up with those same stories about the people around him if he had stayed on his phone or become wrapped up in a conversation of his own?

The great French artist Delacroix was a resolute believer in the value of solitude, and he wrote about the topic in his diary. He also wrote about the problem of distractions. Being a man of the nineteenth century he didn’t write about using his phone as a distraction, as both of the Mueller twins did, but his thoughts on the topic are all the more relevant today when distraction is only one swipe of the finger away. Delacroix wrote:

“Think of the blessings that await you, not of the emptiness that drives you to seek constant distraction. Think of having peace of mind and a reliable memory, of the self-control that a well-ordained life will bring, of health not undermined by endless concessions to the passing excesses which other people’s society entails, of uninterrupted work, and plenty of it.”

Eugene Delacroix, Orphan Girl at the Cemetery, c. 1823-1824, Oil on canvas

The emptiness that drives us to seek distraction is something we have to experience temporarily before we can enter the fertile grounds of creative solitude. Both the fear of appearing to be alone and the boredom of having no one to talk to can block us from entering this place of productive seclusion. Technology, social media, and crowded city spaces also conspire to stop us from entering it. Nevertheless, given how many great artists have sought out private spaces to think and create, it seems that this is a challenge worth taking on.

*Picasso did work alongside other artists, most notably Braque, who were interested in the same ideas, but some of his most generative work was done in solitude.

Amsterdammers

Russell Shorto’s Amsterdam: A History of the World’s Most Liberal City traces the city’s liberalism from the twelfth century when a handful of industrious farmers began piling up dirt to hold back the sea through the miracle in 1345 that made Amsterdam a destination for devout pilgrims, the Protestant Reformation and beginning of religious freedom, the golden age in the 17th century, the horrors of WWII, and the peace-loving, provocative youth culture of the 1960’s that reestablished Amsterdam’s reputation as the center of liberalism.

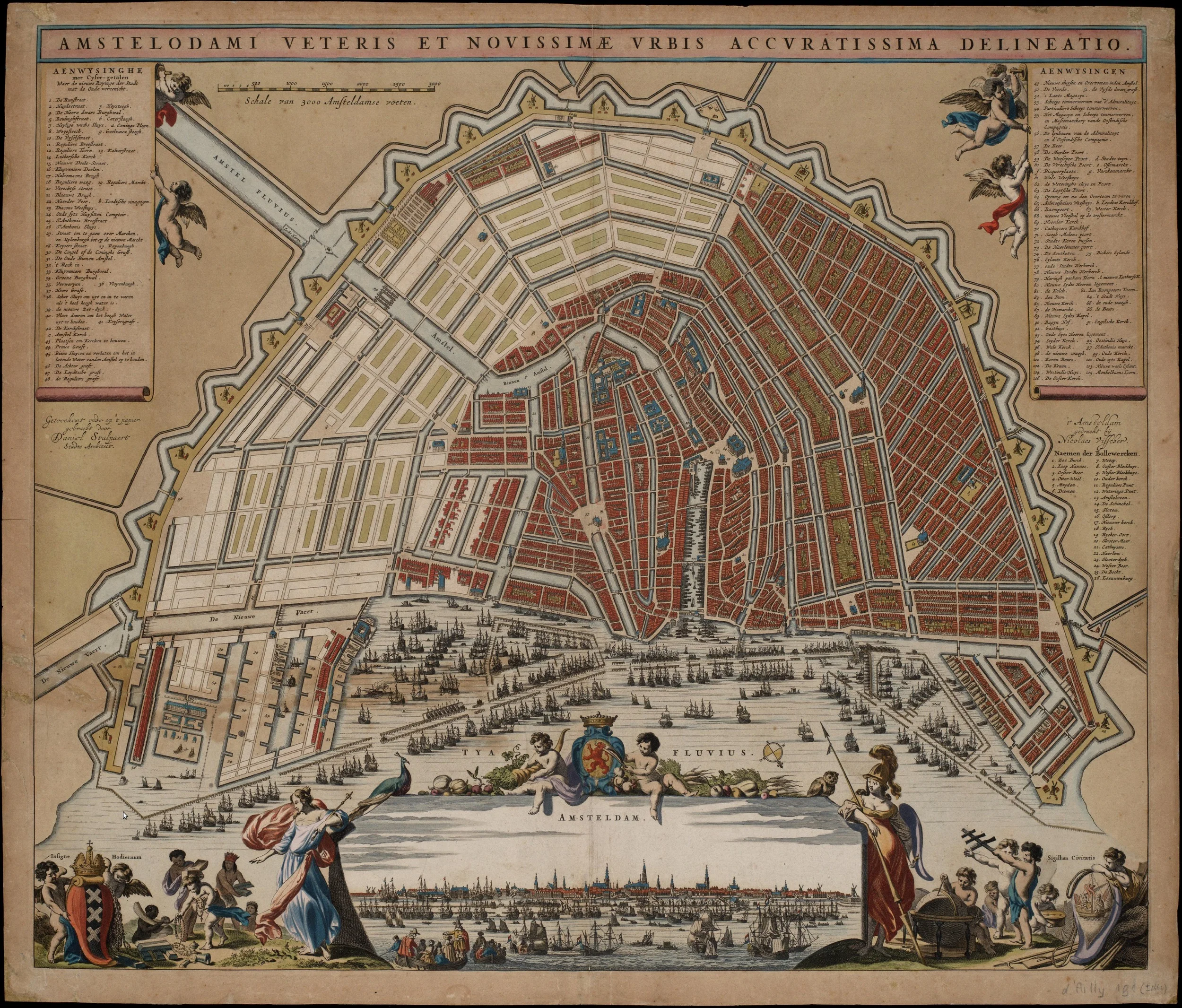

One of Shorto’s main arguments is that the way the canals and solid land were sculpted out of the once-soggy lowlands, a process requiring both autonomy for individuals (who bought the plots of land) and collaboration within the community (which had to build dikes and dams, operate windmills, and dig canals) is key to understanding Amsterdam’s particular brand of liberalism today. During the Middle Ages in other parts of Europe the lord of a manor oversaw the peasants working on his estate; in Amsterdam neither the church nor the nobility owned all the land. Each small plot of earth was reclaimed from the sea by the ingenuity and hard work of the community and then purchased and farmed by the individuals living there. This meant Dutch peasants had no need to adopt an attitude of deferential obedience since they were their own bosses. What they did need to adopt, however, was an attitude of tolerance and cooperation toward their fellow peasants. And, once the city became a center of global trade, they extended this attitude of tolerance toward other types of cultural difference as well.

A map of Amsterdam with its canals from 1662

A canal in modern Amsterdam

While the argument is impossible to prove, it does (to use an idiom appropriate to the marshy lowlands) seem to hold water, and as I read Shorto’s book I became convinced that the unique landscape of the Netherlands played a role in its becoming a place that values both individualism and tolerance for otherness.

As an artist, I’m particularly interested in how the culture of Amsterdam shaped the types of art created there. One of the best-known artists of Amsterdam is Rembrandt van Rijn, who frequently inserted his own visage into his paintings and etchings of Biblical scenes. He also painted some of the most probing and psychologically sophisticated self-portraits any artist has ever made.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait with Beret and Turned-Up Collar, 1659, Oil on canvas

Shorto contrasts Rembrandt’s work with that of earlier artists, particularly Catholic artists working in Italy. He shows that Rembrandt's work was different, in part, because of the individualism and freedom that came with being an Amsterdammer.

“He developed a dexterity with what were called historical paintings. We would call them religious paintings (though some were of mythological rather than biblical subjects), but they were fundamentally different from those of Michelangelo, Raphael, and other earlier artists. Those artists were commissioned by churches and their work was installed behind altars: the artists were workers in the business, the industry, of religion. But these were different times, and this was a different place. The Dutch provinces had broken free of Catholicism and were on a new trajectory, in the service of individuals, which encouraged them in turn to be interested in individuality: their own and that of their subjects. The clients of Dutch artists were not priests and popes but herring wholesalers and flax merchants.”

In the past I’ve often thought about the emotional complexity of Rembrandt’s work, but I had never considered that this emphasis on the interior life of his subjects, including the subject of himself, was partly a product of the culture of Amsterdam. This tendency toward self-examination is particularly apparent in a painting Rembrandt made as a young man, not even twenty years old: his Stoning of Saint Stephen. Shorto points out that Rembrandt included not just one but three self-portraits in this work, since Rembrandt’s face appears on three figures: a saint, the saint’s tormentor, and a figure in between the two of them who stares out at the viewer. Shorto expresses the dynamic between these three representations of Rembrandt well:

“What was going on here? From our psychological perspective, we might say the artist was making a statement or inquiry about himself, the sort of thing that most people at the threshold of adulthood do. He was wondering who he was. Am I a saint or a guilty sinner? Am I someone who violently refutes the manifestation of God’s grandeur? The third painted self, in the traditional stance of staring out at the viewer, which is tucked precisely in between the other two, seems to be posing this quandary, asking the viewer to help him figure himself out. If this is true, then the artist was doing something that is commonplace now but had rarely been done before: using his art for his own emotional needs.”

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Stoning of Saint Stephen, 1625, Oil on canvas

The idea that art can be used in a therapeutic process of self-examination is popular today, so popular it is easy to forget it was ever new. When I’ve asked students why they believe people make art today, one of the most common answers given is self-expression (or some variation of that phrase). We take for granted today the idea that the psyche of the artist is in some way on display when he exhibits his work, and we rarely consider the history of that idea.

Shorto only mentions Vincent Van Gogh briefly in his book, but the parallels between Van Gogh and Rembrandt are hard to ignore: both were prolific painters of the self, both were Dutch, and both were able to pierce through the mere appearance of people and capture their inner life. Van Gogh only lived in Amsterdam for one year, and it was during a period in his life when he was studying for the ministry (something he failed at miserably), not seeking to become an artist, but it is nevertheless possible that he absorbed something of the city’s culture during that short time.

Vincent Van Gogh, Self-Portrait with Straw Hat, 1887, Oil on cardboard

Two quotes from Van Gogh stand out to me as representing both the individualism and attitude toward community that Shorto claims underlie the liberalism of Amsterdam. On one hand, Van Gogh wrote, “An artist needn’t be a clergymen or a churchwarden, but he certainly must have a warm heart for his fellow men.” On the other, Van Gogh also wrote, “I put my heart and my soul into my work, and have lost my mind in the process.” Van Gogh simultaneously reached out to the world around him and also made his own emotional life the subject of his work. He showed acceptance for others in whatever state he found them even as he valiantly sought to express himself as an individual. In that sense, his work embodies what it means to be an Amsterdammer.

Vincent Van Gogh, The Potato Eaters, 1885, Oil on canvas

Henry Frick's Paintings

Whenever I visit The Frick Collection in New York City, I marvel at what it must have been like for Henry Clay Frick, whose mansion and art collection were left to the public after his death in 1919, to own three paintings by Johannes Vermeer. When Frick built his home he already knew he intended for it and his large art collection to become a museum someday, but during his lifetime it was a place of residence. One can imagine him on an ordinary weekday morning finishing breakfast and pausing not to look out the window but to contemplate the expression of a Dutch woman from the seventeenth century as captured by the masterful Vermeer.

Johannes Vermeer, Girl Interrupted at Her Music, 1658-59, Oil on canvas

Johannes Vermeer, Mistress and Maid, 1666-67, Oil on canvas

Johannes Vermeer, Officer and Laughing Girl, 1657, Oil on canvas

Johannes Vermeer, sometimes called the Sphinx of Delft, was a man of mysteries even when he was alive. Few people outside of Delft had heard of him, and his output – a total of 35 paintings – was low. Since then, his riveting work has inspired many other artists and writers, including Tracy Chevalier, who wrote Girl With a Pearl Earring. When the painting that inspired her book was shown in the Frick in 2014, visitors waited outside in long lines in subzero temperatures to see the painting. Another painting in the same exhibit, The Goldfinch by Carel Fabritius, drove even more crowds to the exhibit, since it too was the inspiration for a popular book by Donna Tartt. Since The Goldfinch was on loan from The Hague in the Netherlands, most of these folks would only see it once in their lives – a stark contrast to the experience of Frick who lived with his three Vermeer paintings and saw them daily.

Johannes Vermeer, Girl With A Pearl Earring, 1665, Oil on canvas

Carel Fabritius, The Goldfinch, 1654, Oil on panel

The pleasure of having something forever as opposed to experiencing it once and then holding on to its memory is a complicated one. It is easy for me to imagine that Frick must have gazed intently at his beautiful paintings every day, never wearying of their beauty or mystery. I like to think that he savored them with the same attention that those museumgoers lavished on Girl With a Pearl Earring when they had their first and only glimpse of it. I like to think that Frick’s overall quality of life must have been improved merely by his continual access to such great artwork, that his disposition was permanently changed for the better as a result of these possessions.

In all likelihood, however, living with a great piece of art is not like that. According to the hedonic treadmill theory, when something new – either good or bad – enters our lives, most of us adapt to it quickly and then return to our original level of happiness. In other words, though I can’t believe it is true, owning a painting by Vermeer would probably not make me or anyone else significantly happier overall.

I was thinking about this question – that of what it means to experience a particular joy or pleasure repeatedly – when I was reading C. S. Lewis’ Perelandra the other day. Perelandra is the second book in Lewis’ Space Trilogy and also the name of the fictional planet where the story takes place. The main character, Dr. Ransom, arrives on Perelandra and discovers trees with bubbles hanging from them. Each bubble starts tiny and then grows until it eventually bursts. The following is his account of touching one of the bubbles:

“Immediately his head, face, and shoulders were drenched with what seemed (in that warm world) an ice-cold shower bath, and his nostrils filled with a sharp, shrill, exquisite scent that somehow brought to his mind the verse in Pope, ‘die of a rose in aromatic pain.’ Such was the refreshment that he seemed to himself to have been, til now, but half awake. When he opened his eyes – which had closed involuntarily at the shock of moisture – all the colors about him seemed richer and the dimness of that world seemed clarified.”

The pleasure of touching one bubble on the bubble-tree was so great that Dr. Ransom considered throwing himself at the tree so that all the bubbles would burst over him at the same time, but he thought better of it and exercised restraint, knowing that having more of a thing was not necessarily better. He described his thoughts this way:

“But this now appeared to him as principle of far wider application and deeper moment. This itch to have things over again, as if life were a film that could be unrolled twice or even made to work backwards… was it possibly the root of all evil? No: of course the love of money was called that. But money itself-perhaps one valued it chiefly as a defense against chance, a security for being able to have things over again, a means of arresting the unrolling of the film.”

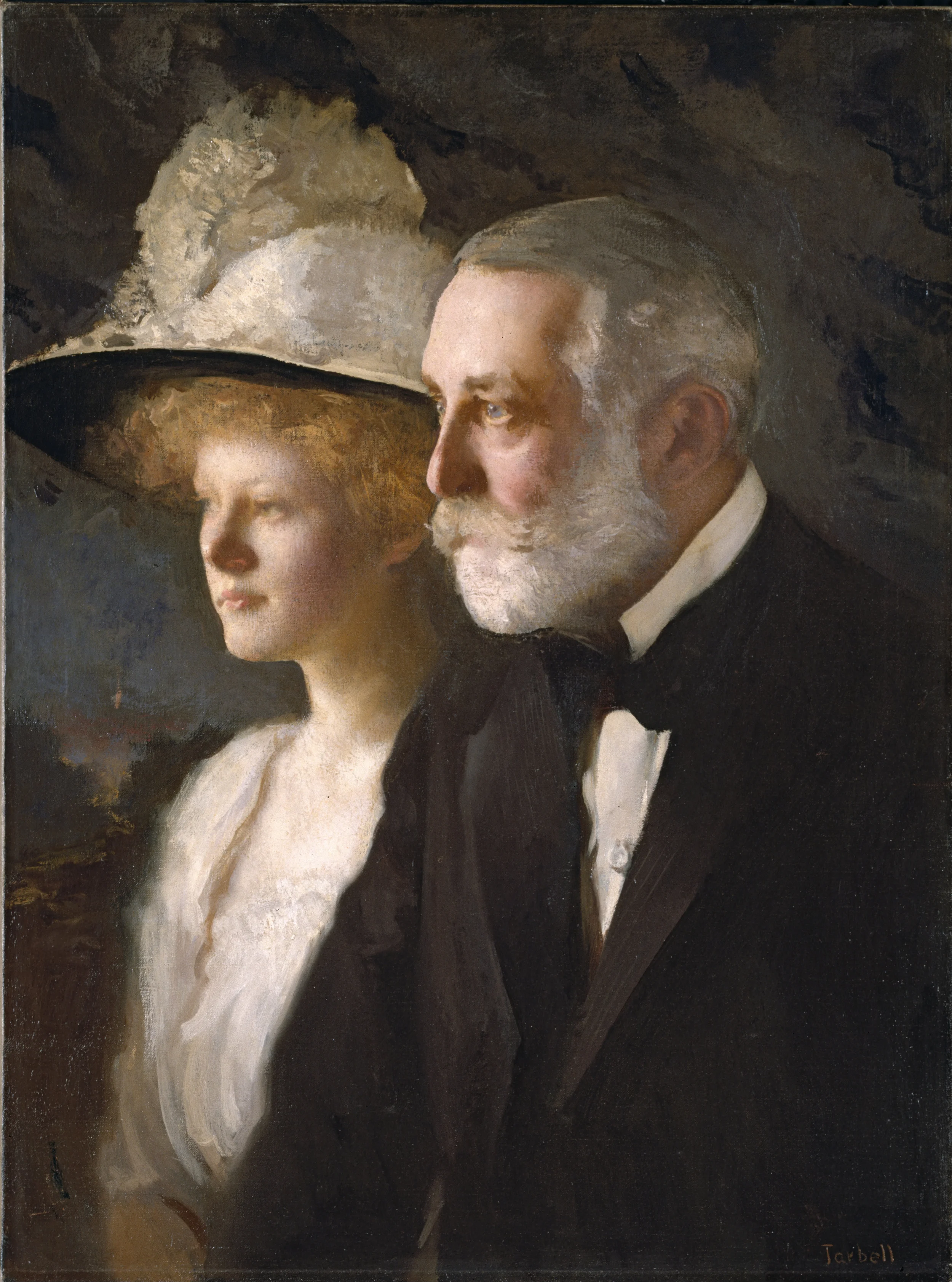

Did Frick love his money? He was certainly a tough businessman. He earned his money first in the coke industry and then later in the steel industry when he became chairman of the Carnegie Steel Company. He was known for being merciless in his dealings with the laborers in the mills, so much so that after a particularly bitter labor strike at one of the steel mills, a man came into his office and shot him. Frick survived, but the story is evidence of the ill will felt toward him.

Edmund C. Tarbell, Henry Clay Frick and Helen Frick, 1910, Oil on canvas

Regardless of whether or not he loved it, his money was the reason Frick owned a mansion full of paintings. His money was the reason that he knew these paintings with the same familiarity that ordinary people today might know the sign at the local pizzeria or the pattern of the slightly faded wallpaper in their dining room. And yet, it is worth asking whether, conceivably, those who wait in long lines to see the paintings only once have it so much worse. After all, these pieces will never fade into the fabric of their quotidian lives; their memory of the pieces will always be that of a fresh and startling first impression.

This is not an argument against owning art. A small or even a large art collection is a wonderful thing, particularly when it is shared with others, as The Frick Collection is now. But art, like other possessions, does not necessarily make us happier or better people. Even if we only see a piece of art on rare occasions, perhaps especially if we only see it on rare occasions, we can still bask in its beauty and mystery. We can still understand, for a moment, why the Sphinx of Delft has inspired so many.